Viruses are scary. They invade our cells like invisible armies, and each type brings its own strategy of attack. While viruses devastate communities of humans and animals, scientists scramble to fight back. Many utilize electron microscopy, a tool that can “see” what individual molecules in the virus are doing. Yet even the most sophisticated technology requires that the sample be frozen and immobilized to get the highest resolution.

Now, physicists from the University of Utah have pioneered a way of imaging virus-like particles in real time, at room temperature, with impressive resolution. In a new study, the method reveals that the lattice, which forms the major structural component of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), is dynamic. The discovery of a diffusing lattice made from Gag and GagPol proteins, long considered to be completely static, opens up potential new therapies.

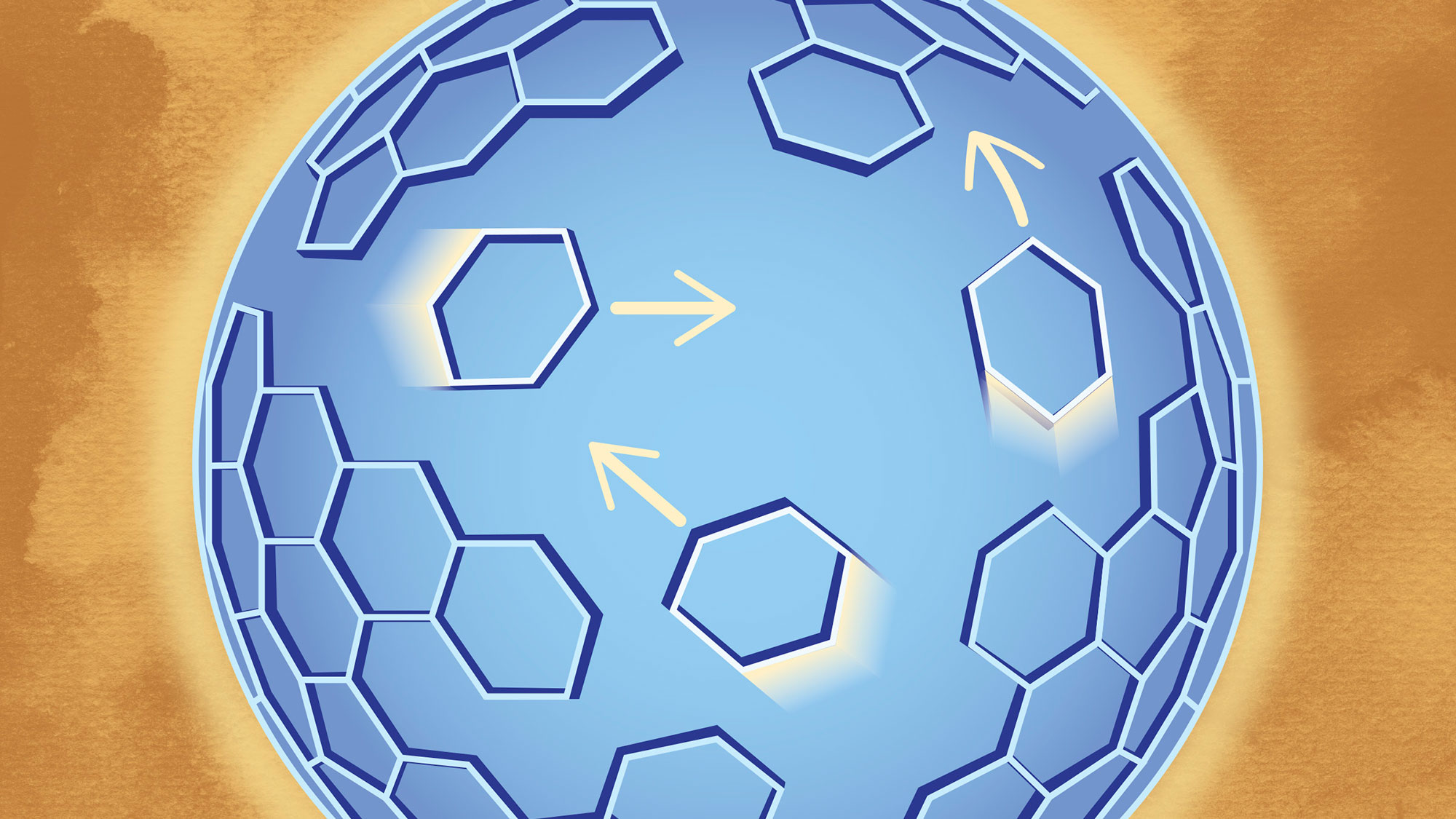

When HIV particles bud from an infected cell, the viruses experience a lag time before they become infectious. Protease, an enzyme that is embedded as a half-molecule in GagPol proteins, must bond to other similar molecules in a process called dimerization. This triggers the viral maturation that leads to infectious particles. No one knows how these half protease molecules find each other and dimerize, but it may have to do with the rearrangement of the lattice formed by Gag and GagPol proteins that lay just inside of the viral envelope. Gag is the major structural protein and has been shown to be enough to assemble virus-like particles. Gag molecules form a lattice hexagonal structure that intertwines with itself with miniscule gaps interspersed. The new method showed that the Gag protein lattice is not a static one.

“This method is one step ahead by using microscopy that traditionally only gives static information. In addition to new microscopy methods, we used a mathematical model and biochemical experiments to verify the lattice dynamics,” said lead author Ipsita Saha, graduate research assistant at the U’s Department of Physics & Astronomy. “Apart from the virus, a major implication of the method is that you can see how molecules move around in a cell. You can study any biomedical structure with this.”

Subscribe to PharmaTutor News Alerts by Email