{ DOWNLOAD AS PDF }

ABOUT AUTHOR

AK Mohiuddin

Department of Pharmacy,

World University of Bangladesh,

Dhanmondi, Dhaka, Bangladesh

ABSTRACT

The term “Home-based care” or simply home care may be defined as a wide array of different types of care provided in the home by a wide range of parties. The continuum of different types of home-based care delivered in the home varies in terms of different dimensions, including acuity, type of care provided, and degree of physician involvement. Home-based care includes both formal and informal personal care services, Medicare skilled home health, physician house calls, and even “hospital-at-home” services. Medication-related issues are basic among home care patients who take numerous medications and have complex medical chronicles and medical issues. The objectives of home social insurance administrations are to assist people with improving capacity and live with more prominent freedom; to advance the customer's ideal dimension of prosperity; and to help the patient to stay at home, maintaining a strategic distance from hospitalization or admission to long-term care foundations. Home care is an arrangement of care given by talented experts to patients in their homes under the bearing of a doctor. Home medicinal services administrations incorporate nursing care; physical, word related, and discourse language treatment; and medical social administrations. Doctors may allude patients for home medicinal services administrations, or the administrations might be asked for by relatives or patients. The scope of home human services benefits a patient can get at home is boundless. Contingent upon the individual patient's circumstance, care can extend from nursing care to specific medical administrations, for example, laboratory workups. Basic analyses among home medicinal services patients incorporate circulatory disease, coronary illness, damage and harming, musculoskeletal and connective tissue disease and respiratory disease.

Reference Id: PHARMATUTOR-ART-2655

|

PharmaTutor (Print-ISSN: 2394 - 6679; e-ISSN: 2347 - 7881) Volume 7, Issue 04 Received On: 16/01/2019; Accepted On: 27/02/2019; Published On: 01/04/2019 How to cite this article: Mohiuddin, A. 2019. Community Liaison Pharmacists in Home Care. PharmaTutor. 7, 4 (Apr. 2019), 1-21. DOI:https://doi.org/10.29161/PT.v7.i4.2019.1 |

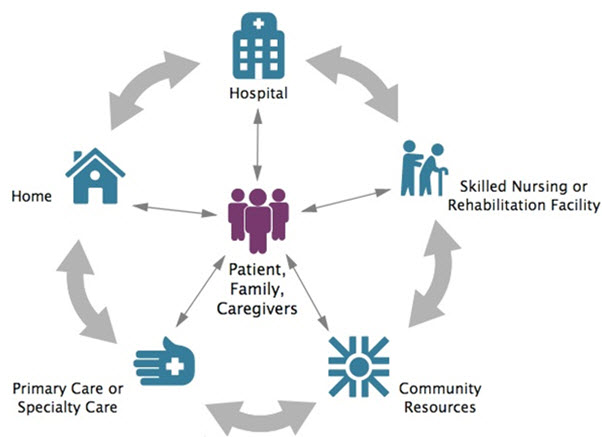

Figure 1. Patient Care Transition from Hospital to Home.

Poor transitions of care between settings can affect patient outcomes, even cause harm. Patients and their caregivers may be confused or overwhelmed, and may not understand what to expect, what medications to take, or how to address their needs during transitions. Poorly executed care transitions can lead to adverse events, unnecessary readmissions, reduced quality of life, and unneeded use of resources. “Transitional care is universal. It doesn't matter whether you have a brain injury, or had a hip replacement, a stroke, or a spinal-cord injury. A smooth transition is really important for reducing the number of re-hospitalizations”--Minna Hong, Patient Partner, Peer Support Manager, Shepherd Center (Web Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute)

INTRODUCTION

The scope of pharmacy services available in home-care continues to expand. Pharmacists provide a wide range of medications, along with health and convalescent aids, for patients at home. Traditionally community pharmacists have been viewed as providers of prescription and nonprescription medications administered orally. Today pharmacists in community and hospital pharmacies across the country have expanded their services for the homebound patient and provide a variety of sophisticated products and services in the patient's home. Community pharmacists provide home health services including medication reconciliation and teaching. Pharmacists must adapt their communication to address the wide variety of patients’ drug-related problems during these home visits and achieve patient-centered communication. Little is known about the topics discussed during a post-discharge home visit and most studies investigating patient-pharmacist communication focused primarily on one-way pharmacist information provision, e.g. the extent to which pharmacists counsel patients, and their communication style, e.g. tone of voice. Patient-centered communication is associated with increased patients’ satisfaction, better recall of information and improved health outcomes and requires active participation of both the pharmacist and the patient. Patients should be encouraged to express their needs and concerns regarding their medication, which pharmacists should address to support patients in making informed decision. Current perspectives to consider in establishing or evaluating clinical pharmacy services offered in a home care setting include: staff competency, ideal target patient population, staff safety, use of technology, collaborative relationships with other health care providers, activities performed during a home visit, and pharmacist autonomy. Gaining insight in the communication during these home visits could be valuable for optimizing these visits; and consequently, to improve patient safety at readmission to primary care. A home visit protocol enables pharmacists:

• To address known major challenges during the transition from hospital to primary care

• To address patient’s dissatisfaction about health care is important as it facilitates patient participation during consultation and acceptance of pharmacists’ advices

• To discuss patients’ medication beliefs and adherence issues more frequently, which might be facilitated by additional pharmacist training and increasing patient engagement.

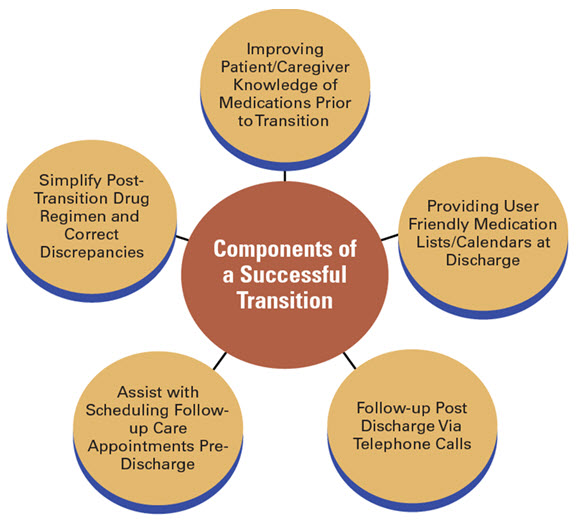

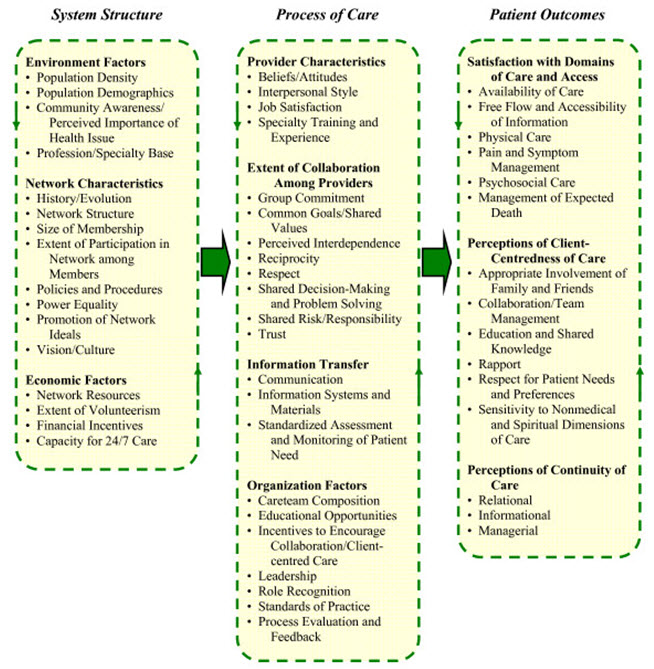

Figure 2. Elements of successful transitional care models. The care plan should include how these needs would be met and by whom. After older persons are discharged from hospital and back at home again, they often have to adjust and cope with possible repercussions due to illness and health problems. Many encounter a variety of problems within the first week back at home, a particularly vulnerable period. The most commonly reported overall adverse event for older persons in several countries is related to medicine treatment, which also causes a considerable number of readmissions. Therefore, competence among involved care professionals has been shown to Moreover, collaboration and multidisciplinary approaches are also highlighted as well as communication among professionals (Rydeman, 2012)

Client Recruitment and Home Visits

Upon admission to the office, any home care customer taking at least nine medications, including over-the-counter and herbal items, is offered a pharmacist home visit. Prior to the home visit, the pharmacist audits the customer's rundown of requested medications and graph notes from other home care clinicians, for example, attendants, word related therapists, and physical therapists. Amid the home visit, the pharmacist examines each drug, including over-the-counter items and herbal enhancements, with the customer and caregiver to evaluate their sign, adequacy, well-being, and consistence, including reasonableness. After the main home visit, the pharmacist contacts the customer's prescriber with any suggestions for upgrading drug therapy. This correspondence is finished by electronic wellbeing record, phone, or fax. Basic proposals incorporate ceasing pointless or copy therapies or changing medicine portions. Follow-up care is composed by the pharmacist and nurse (Shanon et.al., 2013).

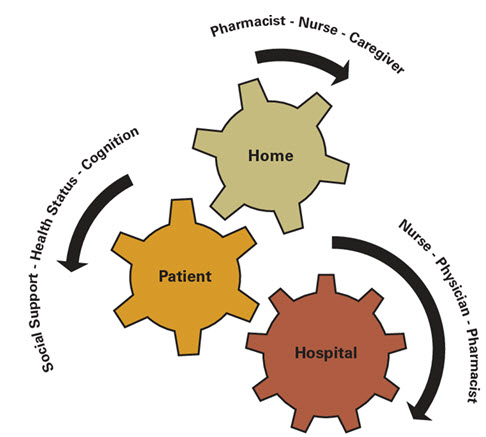

Figure 3. Cogwheels of Transition.

Each and every cog must be synchronized and appropriately placed for a seamless, effective and safe care transition. During times of transition, the pharmaceutical care patients receive is often suboptimal and wrought with danger. Home healthcare nurses play a pivotal and important role in providing transitional care to patients by identifying and resolving medication discrepancies. Nurses must partner with pharmacists, physicians, and others involved with care transitions to decrease the likelihood of patients experiencing untoward health consequences associated with medications. (Setter et.al., 2012).

Benefits of the Pharmacy Home Visit Program

Although nurses and therapist, depending on client need and orders, assess all of a client's needs, the pharmacist is able to focus primarily on medications. Through the MOCH program, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians working with their health and social care colleagues and care homes staff, patients and their families, can provide a number of benefits for care homes and their residents including:

• Optimizing medicines (stopping inappropriate or unsafe medicines, and ensuring medicines add value to patient’s health and well-being)

• Patient centered care (shared decision making about which medicines care home residents take and stop)

• Creating better medicines systems for care homes to reduce waste and inefficiency

• Training and supporting care home staff to enhance safer administration of medicines (NHS England).

• Available studies have shown decreased health care utilization, decreased costs to the health system, and improved medication management with pharmacy involvement in home care.

• Beneficial patient outcomes of pharmacy practice in home care settings, such as decreased hospital admissions, decreased emergency department visits, improved quality of life, improved compliance, and decreased adverse events, have been described in many developed countries.

• Positive effects of pharmacy practice in ambulatory care settings, such as decreased benzodiazepine use, improved anxiety scores, improved cardiac outcomes, and improved compliance.

• Most home care pharmacy programs in developed countries provide several services, including comprehensive or targeted medication reviews; education for patients, families, and staff; and provision of drug information (Walus et.al., 2017).

Figure 4. Flow diagram of Refer-to-Pharmacy and Pharmacy Home visit Protocol. Once a referral is accepted, the community pharmacist can then contact the patient to arrange a mutually convenient time for them to visit the pharmacy for their consultation. The pharmacist may then prepare effectively for the consultation as they have a copy of the patient’s discharge letter. The strap line for Refer-to-Pharmacy is “get the best from your medicines and stay healthy at home” which in lay speech means “medicines optimization”. In March 2015 the NICE published Medicines Optimization guidance, which amongst other things states: “a consenting person’s medicines discharge information should be shared with their nominated community pharmacy”. Refer-to-Pharmacy provides the tool to make this possible, and to so routinely for every eligible patient (Gray, 2015).

Common MRPs and Success of Pharmacy Visits at Home

Traditionally, nursing homes have been associated with suboptimal drug therapy and MRPs. In contrast, less is known about drug safety in homecare. Significantly more MRPs were detected among patients receiving home nursing care than patients living in nursing homes. While patients living in nursing homes were often undermedicated, documentation discrepancies were more frequent in home-nursing care. MRP categories leading to changes on the medication lists differed between the settings.

• Untreated conditions: The patient has a medical condition that requires drug therapy but is not receiving a drug for that condition.

• Drug use without indication: The patient is taking a medication for no medically valid condition or reason. For example, a client may be taking proton-pump inhibitor although he or she does not have a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease or peptic ulcers. Conversely, a client with hypertension and diabetes mellitus may not be taking aspirin, although he or she has an indication for it.

• Improper drug selection: The patient’s medical condition is being treated with the wrong drug or a drug that is not the most appropriate for the patient’s special needs.

• Subtherapeutic dosage: The patient has a medical problem that is being treated with too little of the correct medication.

• Overdosage: The patient has a medical problem that is being treated with too much of the correct medication.

• Effectiveness: Effectiveness-related problems occur when a medication dose is too low or when a more effective drug is available. For example, a patient with chronic pain may be taking acetaminophen when an opioid may be more effective.

• ADRs: The patient has a medical condition that is the result of an adverse drug reaction or adverse effect. In the case of older adults, adverse drug reactions contribute to already existing geriatric problems such as falls, urinary incontinence, constipation, and weight loss.

• Safety: When a client is taking a medication with a dose that is too high or is taking a medication that causes an adverse drug reaction, he or she is experiencing a safety medication-related problem. For example, a client may not be able to take amitriptyline for insomnia because anticholinergic side effects are too bothersome.

• Drug interactions: The patient has a medical condition that is the result of a drug interacting negatively with another drug, food, or laboratory test.

• Compliance: The patient has a medical condition that is the result of not receiving a medication due to economic, psychological, sociological, or pharmaceutical reasons. Compliance-related problems describe instances when a client prefers not to take a medication, does not understand how to use a medication, or cannot afford a medication. A client is experiencing a compliance-related problem if he or she does not understand how to use an inhaler or prefers not to take a medication to treat a condition (Shannon et.al., 2013; Walus et.al., 2017; Wolstenholme, 2011).

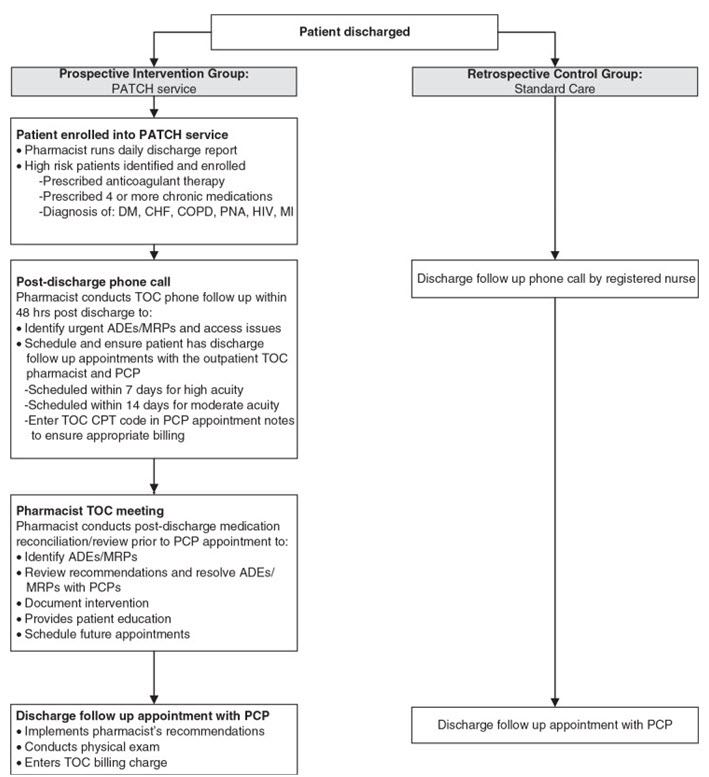

Figure 5. Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH)

service workflow depicting steps to optimize medication safety for high-risk patients. During the pharmacist meeting, a comprehensive medication review, BP and glucose log review, medication reconciliation, and allergy assessment are performed. Additional patient education is provided through verbal discussion and disease state management pamphlets. The pharmacist then discusses all MRPs identified with the PCP immediately after the pharmacist session and a medication plan is formulated. Recommendations are also documented within the EMR in the PCP encounter and are available for the PCP to review prior to the face-to-face visits with the patients. After the PCP visit, patients are provided with a post-visit summary sheet reinforcing educational points from both the pharmacist and PCP sessions as well as an updated medication list. Follow-up visits with the pharmacist are scheduled, if the patient requires additional education and/or management based on the clinical judgment of the PCP or pharmacist (Trang et.al., 2015).

The core of the PATCH service is the ability of pharmacists to provide comprehensive patient-centered care by identifying MRPs and making evidence-based recommendations to providers to optimize medication use. MRPs have been estimated to cost approximately $177.4 billion per year and are estimated to be one of the top 5 causes of death in the elderly population. Identifying, resolving, and preventing MRPs can lead to cost savings as well as improved patient outcomes (Devik et.al., 2018; Trang et.al., 2015). Traditionally, the availability of clinical pharmacy services has been in the purview of hospitals where increased clinical pharmacy services has been associated with reduced length of stay and mortality. Recognition of the value of the role of the pharmacist has resulted in expansion of clinical services into outpatient settings, including patient homes. For example, the HMR program that was established in Australia in 2001 provides funding for pharmacists to visit patients at home to assess their medication regimens. In Canada, provincial governments are compensating pharmacists for providing medication reviews (MRs) for non-hospitalized patients and also authorizing pharmacists to prescribe (Flanagan, 2018).

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Residential Care Pharmacists into Aged Care Homes

Prescribing in the residential aged care population is complex, and requires ongoing review to prevent medication misadventure. Integrating an on-site clinical pharmacist into residential care teams is an unexplored opportunity to improve quality use of medicines in this setting. Pharmacist-led medication review is effective in reducing medication-related problems; however, current funding arrangements specifically exclude pharmacists from routinely participating in resident care (McDerby et.al., 2018).

Medication Use in Older Adults

Prescribing in the older population is highly complex. Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes lead to variations in drug bioavailability, increased drug sensitivity, and decreased regulatory mechanisms, altering the effects of drug usage from those observed in younger populations. In addition, the presence of multiple co-morbidities necessitating multiple medication usage equates to an increased risk of medication misadventure in older adults. Advancing age is positively correlated with increased prevalence of chronic disease, and increased number of co-morbidities correlates with increased medication use (Corsonello et.al., 2010; Mangoni et.al., 2004; Fernandez et.al., 2011; Chen, 2016; Payne et.al., 2014). ADEs can significantly impair occupational and cognitive functioning, and quality of life. All medications have the potential to cause an ADE, particularly in older adults, as a result of pathophysiological decline, inappropriate polypharmacy, and involvement of multiple health providers. This can worsen cognitive impairment, frailty, disability, frequency of falls, and mortality (Chen, 2016; Payne et.al., 2014).

Transitions of Care and ADEs

Transitioning into aged care has been identified as a particularly high-risk point where residents are vulnerable to medication errors and ADEs. Transitions of care for residents include new admission from the community or hospital to a RACH, or returning to the RACH post-discharge from hospital. Poorly executed care transitions and miscommunication can result in interrupted continuity of care and adverse events, which may lead to inappropriate re-admission to hospital or presentation to emergency departments. A study shows Hypertension (nearly 50%%) was the highest prevalent chronic disease among the study participants followed by osteoarthritis (35%), diabetes mellitus (more than 25%), respiratory disorders (14%) and cerebro-vascular accidents (11%) in old-age homes of Malaysia. Approximately 20% of residents experience a significant delay in medication administration and missed doses following admission or re-admission to a RACH. Transition-related medication errors are observed in 13–31% of RACH residents, often involve high risk medications, such as warfarin, insulin, psychoactive agents, and opioids, and have greater risk of causing serious harm to the resident (Tong et.al., 2017; Deeks et.al., 2015 Ferrah et.al., 2016; Sugathan et.al., 2014)

Communicable Disease Prevention

Five most common infections in the elderly are UTIs, GI infections, Bacterial pneumonia and influenza. Viral infections like herpes zoster (shingles), pressure ulcers, bacterial or fungal foot infections (which can be more common in those with diabetes), cellulitis, drug-resistant infections like MRSA are common skin infections. More than 60% of seniors over 65 get admitted to hospitals due to pneumonia, reported by AAFP (underlying causes are changes in lung capacity, increased exposure to disease in community settings, and increased susceptibility due to other conditions like cardiopulmonary disease or diabetes). Influenza and pneumonia combined add up to the sixth leading cause of death in America — 90% of these in senior adults. Weakened immunity in the elderly, along with other chronic conditions, increases the risk of developing severe complications from influenza, such as pneumonia. Because influenza is easily transmitted by coughing and sneezing, the risk of infection increases in a closed environment like a nursing home. Cough, chills and fever are the common symptoms, though, again, influenza may present different signs in older adults. Influenza is largely preventable through annual vaccination, and there is sufficient evidence to support RACH staff vaccination to protect residents from influenza. The rational for this is to improve accessibility to the vaccination for members of the community who have difficulty accessing the vaccine through their GP or employer, as pharmacies are often open later and on weekends (Simonetti et.al., 2014; Stevenson, 2017; Cascini et.al., 2013; Manabe et.al., 2015).

Terminal/Palliative Care

Palliative care in U.S. hospitals increasing every year, according 2018 Palliative Care Growth Snapshot issued by the CAPC. The prevalence of hospitals (50 or more beds) with a palliative care team increased from 658 to 1,831–a 178% increase from 2000 to 2016 (CAPC Press Release, 2018). And By 2056, 480,000 Canadian deaths per year are predicted with 90% of those deaths being eligible for palliative care (Hofmeister et.al., 2018). Patients diagnosed with a terminal illness often require nonstandard doses that are not available commercially, so pharmacists caring for hospice patients may need to compound products to meet individual patients’ unique needs (Demler, 2016; Medscape Pharmacists, 2007). This may include formulating preparations that are flavored to overcome undesirable characteristics or producing dosage forms with alternative ingredients and/or excipients to avoid allergic reactions or progressive intolerances. Pharmacists can often recommend dosing devices that help patients and caregivers deliver the proper dose of highly potent medications. Such devices might not otherwise be readily available to patients in the community (Mohiuddin, 2019).

Figure 6. Conceptual framework of an integrated palliative care networks.

Realizing dying peoples' needs for complex regimens of treatment and social support in a seamless, fiscally responsible manner, and the difficulty of organizing these services in the community are major drivers of the impetus for multi-level strategies to better coordinate palliative care. This has fueled global interest in integrated service delivery, involving the implementation of collaborative, responsive, cost-effective systems of care at the local level. With the increasing prominence of integrated service models in palliative care, and the precarious nature of these arrangements, there is a need for a comprehensive conceptual framework to better understand the structure, process, and outcome functioning of these systems of care. In many counties such as Canada, Netherlands, Australia, and the UK, these integrated systems of care have been mandated by formal policy initiatives in the form of regional palliative care networks (Bainbridge et.al., 2010).

Medication Dispensing for Terminal/Palliative Care

Most palliative pain medications are controlled substances and are registered among the most highly controlled Schedule II drugs. IAHPC identified 21 symptoms and included 33 essential medications for control of these symptoms. In addition, according to a recent study based on international expert consensus opinion, four essential drugs were used for alleviation of anxiety, dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, pain, and respiratory tract secretions, as well as terminal restlessness. These include morphine, midazolam, haloperidol, and an antimuscarinic, which should be offered in the last 48 hours of life for patients with cancer (ASHP, 2002; Lee et.al., 2013). Futile medication use in management of terminally ill cancer patients has also been reported, one-fifth of cancer patients at the end of their life took futile medications. Statins met futility criteria in 97% of cases, gastric protectors in 50%, antihypertensive agents in 27%, antidiabetic prescriptions in 1%, bisphosphonates in 26%, and antidementia drugs in 100% of patients. Unlike chemotherapy, there is no framework in place to validate halting radiation therapy either in the name of overutilization or futility (Gonçalves et.al., 2018; Patel, 2013)

Non-Traditional Administration Routes

Alternative administration routes for palliative care are vital to providing effective patient care. Many commonly prescribed drugs (eg, promethazine, morphine sulfate) may be used in nontraditional routes (Masman et.al., 2015). Topical gels containing metoclopramide, diphenhydramine or lorazepam may found worthful for patients with refractory nausea and vomiting (Del Fabbro, 2016; Grönheit et.al., 2018) Commonly prescribed medications can have nontraditional uses and rectal bioavailability, such as carbamazepine/Topiramate/Lamotrigine tablets or suspension for convulsions; rectal use may allow rapid absorption and partially avoid first-pass metabolism due to rectal venous drain (Walker et. al., 2010). If necessary, drugs can be compounded into parenterals, solutions, creams, ointments, and transdermal dosage formulations to improve patient adherence and ameliorate AEs, such as constipation, nausea, gastrointestinal issues, and sedation (Glare et.al., 2011). Various dosage forms, including transdermal patches of scopolamine and depot injections of octreotide, are used to treat specific needs of individual patients (Erichsén et.al., 2015).

Gastrointestinal Issues

Gastrointestinal issues may develop secondary to many chronic conditions (eg, advanced cancer, neurologic disorders). Constipation is one of the most common problems patients experience at the end of life. The cause can be as simple as dietary alterations or the inability to ambulate or exercise. Severe discomfort and pain from constipation may cascade into an unrelenting decline in a patient’s quality of life, requiring pharmacologic intervention. Privacy issues during toileting and the inability to complete defecation without assistance may progress as a chronic disease worsens, with the proportion of people with severe problems increasing as death approaches (Clark et.al., 2012). Pharmacists can play an important part in preventing and managing the symptoms of constipation, such as bowel obstruction, dehydration, loss of appetite, mobility issues, and medication AEs. Many non-pharmacologic approaches (e.g, dietary changes, avoidance of negative environmental stimuli, behavioral measures such as relaxation) may assist patients without adding to the pharmacologic burden (Goodman et.al., 2005).

Individualized Care or PCC

The point of palliative care is to enhance the personal satisfaction of patients and families through the anticipation and help of anguish. Palliative care in the home is the arrangement of specific palliative consideration in the patient's home, regularly given by attendants as well as doctors with or without association with a doctor's facility or hospice. In a study of 1200 Canadians, more prominent than 70% of respondents wanted to be at home close demise (Wilson et.al., 2013). Since palliative consideration regimens are very individualized to address every patient's issues, coordinating a pharmacist into the interdisciplinary group is fundamental to accomplishing a patient's consideration objectives. Body energy and volume of circulation are changed in patients in end-of-life care.

Role of The Caregivers

Home care clinicians in the WRHA currently rely on community pharmacists for assistance with medication-related issues. According to NCCN “Palliative care specialists and interdisciplinary palliative care teams, including board-certified palliative care physicians, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants, should be readily available to provide consultative or direct care to patients/families who request or require their expertise,” (NCCN, 2013). Pharmacists have an exceptional learning base for improving patient consideration while diminishing AEs and toxicity (Hofmeister et.al., 2013; NCC-C, 2012). Palliative care uses a team approach, including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and pharmacists. The pharmacist's role within palliative care teams is increasing and initial favorable outcomes have been reported. Analysis of patients with known date of first pharmacist visit found significantly improved LOS, LTC, and CTD for patients with early access to palliative pharmacy (in addition to the other members of the palliative team) compared to those without early access (Atayee et.al., 2018). Community pharmacies are suggested to consider stocking the five “essential” palliative care drugs: clonazepam 1mg/ml, morphine 10mg/ml, haloperidol 5mg/ml, metoclopramide 10mg/2ml, and Hyoscine butylbromide 20mg/ml (Haggan, 2017; Tait et.al., 2014). Know About Caring for Children According to the Picker Institute and Harvard Medical School has delineated following dimensions of patient-centered care, including:

• Respect for the patient's values, preferences, and expressed needs

• Information and education

• Access to care

• Emotional support to relieve fear and anxiety

• Involvement of family and friends

• Continuity and secure transition between health care settings

• Physical comfort

• Coordination of care (Davis et.al., 2005)

Clinicians Involved in PPC

Palliative care clinicians are also called to assist with pediatric-aged patients. The PPC team includes multiple disciplines, community-based resources, and family members. Due to advancing technology and medical expertise, children are living longer and with greater medical complexities. Accurate prognostication in pediatrics is complicated by the lack of empirical research and heterogeneous medical experiences. Understanding a family’s narrative about their child’s illness and their definition of quality of life is essential for effective goals of care discussions. Children are not small adults. Developmental differences among infants, children, and adolescents that affect diagnosis, prognosis, treatment strategies, communication, and decision-making processes present challenges to adult providers who do not have training or experience in caring for children. Most symptoms for pediatric patients can be managed analogous to that of adult patients; however, complex neurologic symptoms and feeding difficulties are prevalent and distinct in pediatric population. Families of pediatric patients often choose to accept the burdens involved in the use of life-sustaining technology for the benefit of a longer life for their child. Children develop increasing decision-making capacities as they get older and should have increasing roles in healthcare decisions. Their understanding of illness and death evolves over time (Jordan et.al, 2018; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2009). NHPCO’s Quality Partners program utilizes the Standards of Practice as its foundation to provide a framework for quality assessment and performance improvement.

Transition of Care: Issue of Collaboration

Improving medication management during care transitions will require 3 main initiatives. First, the patient must remain the central focus of care. Second, interprofessional communication and collaboration need to occur among all providers involved in the health care of individual patients. Third, the outcomes of pharmacist involvement during care transitions needs to be evaluated systematically (ideally in controlled trials) to demonstrate a cost-effective improvement in quality and to provide financial justification for investing in pharmacist resources. Collaboration between hospital and community pharmacists can also facilitate patient-centered care. Multiple medication changes during hospitalization can be confusing to patients, caregivers, and providers, and can lead to medication errors. Hospital pharmacists can provide a reconciled medication list and meet with patients for counseling and education. Typically, the day of discharge is busy, and patients have limited time and attention to discuss important issues. A “hand-off” or pharmacist discharge care plan could facilitate the coordination of medication management between the hospital and community pharmacist. This provides continuity so that the community pharmacist has a list of actual or potential medication-related problems to follow-up on with the patient or other health care providers. It also provides the community pharmacist with patient information that they would not normally have access to (Kristeller, 2014). Resources should be targeted toward patient populations at increased risk for readmission, such as patients with heart failure, COPD, asthma, advanced age (discussed earlier), low health literacy, and frequent hospitalizations (FEs).

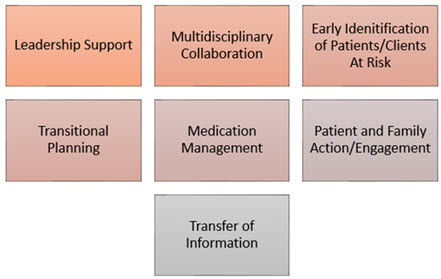

Figure 7. The Seven Elements for a Safe Transition to Occur.

Seven elements that must be in place for a safe transition to occur from one health setting to another include: leadership support; multidisciplinary collaboration; early identification of patients/clients at risk; transitional planning; medication management; patient and family action/engagement; and the transfer of information. The Joint Commission has incorporated transition measures into their disease specific care certification programs as a component to ensure excellence in the delivery of healthcare services for several designated conditions. The Joint Commission have developed videos to help clinicians improve patient transfer communication skills www.jcrinc.com/improving-transitions-of-care-videos/ (DelBoccio et.al., 2015).

Heart Failure Management

Community pharmacists who expand their roles and make home visits to heart failure (HF) patients after hospital discharge can improve outcomes. Home health care teams rarely include pharmacists when they provide care to patients undergoing transitions in care. HF affects approximately 6 million adults in the USA, with more than $30 billion in associated annual costs; by 2030, these figures are expected to rise to more than 8 million adults and more than $69 billion. From 2012 to 2014, the age-adjusted rate of HF-related deaths per 100,000 people increased from 81.4 to 84.0. The impact of pharmacist intervention was evaluated in a pharmacy-led TOC program for patients with HF from a US hospital. The goal of TOC is to help recently-discharged patients avoid unnecessary hospital and emergency room re-admissions while ensuring quick healing and recovery right at home. Their primary functions are in-home medical care, collaboration and communication with patient’s primary care provider, specialist and discharging hospital, discharge summary review, lab testing & diagnostic imaging, medication reconciliation & adherence etc. Admission medication reconciliation and discharge medication review were performed to monitor for appropriateness and dosing, duplications, omissions, and drug interactions. Pharmacy-led TOC increased compliance with HF core measures (including appropriate medication use) and reduced HF readmissions, 30-day readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and costs (Wick, 2015; Anderson et.al., 2018; Mason, 2016).

COPD Management

COPD, the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, is also a major cause of chronic morbidity all over the world, particularly in developing countries. In 2016, it was the third leading cause of years of life lost and disability-adjusted life-years in the United States, with an estimated 164 000 deaths. Indeed, in 2012, more than 3 million people worldwide died of COPD, equating to 6% of all deaths globally in that year. In the UK, the costs associated with COPD are estimated to exceed £800 million. In the USA, more than 26 million people are estimated to have COPD but almost half of these are undiagnosed. The significance of effective COPD exacerbation management is critical to managing healthcare resources. Clinical improvement depends on many factors such as drug selection, patient compliance and control of other risk factors including the environment and nutrition. Patients at risk for having an exacerbation of COPD should receive self-management strategies. Prompt therapy prior to exacerbations reduces hospital admissions and readmissions, speeds recovery, and slows disease progression. COPD patients tend to have better medication adherence with pharmacist counseling, subsequently improving their quality of life as well as clinical outcomes. Direct education by pharmacists has been shown to be more effective than other teaching methods, including watching videos and providing inhaler pamphlets. With increasing number of COPD patients, individualized counseling for patients is a challenge to the limited number of physicians. Incorrect use of inhalers is very common and subsequently leads to poor control of COPD. Pharmacist-led comprehensive inhaler technique intervention program using an unbiased and simple scoring system can significantly improve the inhaler techniques in COPD patients. A 3-month combined program of transition and long-term self-management support resulted in significantly fewer COPD-related hospitalizations and emergency department visits and better HRQL at 6 months after discharge (Boylan et.al., 2018; Nguyen et.al., 2018; Mekonnen et.al., 2016; Aboumatar et.al., 2018; Rinne et.al., 2018; Rose et.al., 2018; van der Molen et.al., 2016).

| Exhibit 1. Frequent Hospitalization and Risk of AECOPD (Wei et.al., 2017) |

| Frequent exacerbations (FEs) mean that the disease is progressing faster, increasing the risk of acute re-exacerbation and mortality. Recent studies showed that ≥2 events/year of AECOPD or ≥1 event/year of AECOPD leading to hospitalization was the risk factor for future exacerbation events. The COPDGene study showed that wall thickness and emphysema were involved in AECOPD and were independent of airflow limitation. Among others, wall thickness and EI, two imaging features, are well-accepted indicators reflecting the pathological changes of COPD. Exacerbation hospitalizations in the past year and EI were independently associated with hospitalization. A cohort study shows that with the increase in the number of hospitalizations, the risk of acute exacerbation and death increased in turn. |

Hip/Knee Arthoplasty

THA and TKA, collectively known as TJA, are beneficial and cost-effective procedures for patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis. The US health care system is the costliest in the world – accounting for 17% of GDP – estimates that percentage will grow to nearly 20% by 2020. TJA is the single largest cost in Medicare, with reports showing a $13.43 billion annual price tag for THAs, and a $40.8 billion annual price tag for TKAs. 20% of readmissions occur due to a medication error, 60 % of all medication errors occur during times of care transitions. The most common cause of unplanned readmission at both 30 and 90 days post-THA were joint-specific reasons, including dislocation and joint malfunction. The second and third most common causes for unplanned readmission, again at both 30 and 90 days, were surgical sequelae and thromboembolic disease, followed by surgical site infection. the pharmacologic intervention directly related to the procedure post-surgery is often limited to pain management (most commonly opioid analgesics). Unlike chronic disease management, the effect of proper pain manages - mint tends to be more tangible to the patient. When non-adherent to the pain management regimen, the resulting symptoms tend to be incentive enough for the patient to become adherent until the operative pain is resolved permanently (Boyle et.al., 2017; Mansukhani et.al., 2015; Batey, 2016; Patton et.al., 2017; Sen et.al., 2014).

Transitional Care Needs of LHL in Hospitalization

Hospitalization represents a crucial care transition point for patients with exacerbations of chronic disease, in which patient education can aid in improving disease management and reducing negative health outcomes after discharge, such as readmissions and discharge medication errors. Resources may be limited for in-hospital patient education, so triaging by HL level may be necessary for resource-optimization. LHL affects approximately 30% to 60% of adults in the US, Canada, Australia, and the EU. Screening for inadequate health literacy and associated needs may enable hospitals to address these barriers and improve post-discharge outcomes. Health literacy is associated with many factors that may affect successful navigation of care transitions, including doctor-patient communication, understanding of the medication regimen, and self-management). Research has also demonstrated an association between low health literacy and poor outcomes after hospital discharge (misunderstanding discharge instructions, poor self-rated health, self-efficacy, and decreased use of preventative services), including medication errors, 30-day hospital readmission, and mortality. Potential ADEs are also common and arise from unintentional discrepancies between admission and discharge regimens, such as changes in dose, route, or frequency, and/or introduction of new medications. Transitional care initiatives have begun to incorporate health literacy into patient risk assessments and provide specific attention to low health literacy in interventions to reduce adverse drug events and readmission. Patients – particularly those with limited health literacy – found a hospital pharmacist-based intervention to be very helpful and empowering. The PILL-CVD study consisting of pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation, inpatient pharmacist counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and individualized telephone follow-up, on the number of clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge suggested more involvement of pharmacists and opportunities for better outcome (Farris et.al., 2014; Louis et.al., 2016; Rowlands et.al., 2015; Cawthon et.al., 2012).

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) and Transition Care

In the case of non-ESRD CKD, the utilization of HC may vary based on patient’s age and comorbidities and, in the case of ESRD, it may vary based on the severity of illness and therapy type. Providing end-of-life care to patients suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD) and/or end-stage renal disease often presents ethical challenges to families and health care providers. Approximately 40% of patients >75 years of age are affected by CKD, and dialysis initiation is highest in patients ≥65 years of age (Davidson et.al., 2013). Many patients who receive dialysis also suffer from multiple comorbidities, and 1-year mortality rates following initiation of dialysis is 41% in patients ≥75 years of age (Rak et.al., 2017). HC services may help in supporting ESRD patients who have chosen conservative care. Up to 15% of older adults with CKD stage 5 opt for conservative management, with conservative management increasingly being recognized as an acceptable and beneficial treatment option (Tonkin-Crine et.al., 2015). The independent treatment modalities for ESRD (peritoneal dialysis, PD, and home hemodialysis, HHD), emphasized as viable alternatives to facility-based treatment modalities over the last decade, are less costly to direct service providers, with equivalent or superior patient outcomes and quality of life (Aydede et.al., 2014). Having an interdisciplinary palliative team in place to address any concerns that may arise during conversations related to end-of-life care encourages effective communication between the patient, the family and the medical team. One aspect that remains largely unaddressed at a systemic level is the high-risk transition period from chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury to permanent dialysis dependence. Incident dialysis patients experience disproportionately high mortality and hospitalization rates coupled with high costs (Bowman et.al., 2018).

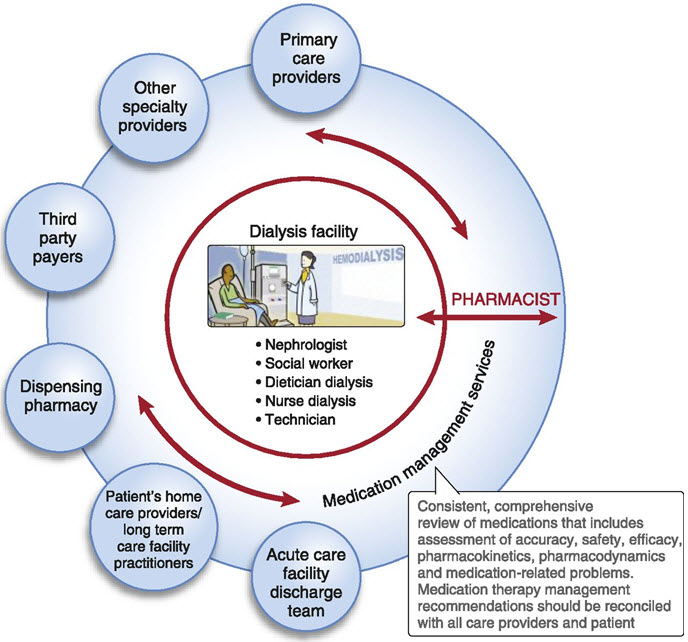

Figure 8. Dialysis facility-centered medication management services model. In this model of care delivery, a pharmacist can provide crosscutting medication management services by communicating bidirectionally between the dialysis unit team and the patient’s care providers, family, and payers, closing the loop of communication, improving medication list accuracy, and identifying and resolving MRPs. The pharmacist in this model could function like a consultant, providing medication management services to patients in several dialysis units (Pai et.al., 2013).

Prevention of Hospital Readmissions

Most common cases of hospital readmissions in US are heart failure, heart attack, and pneumonia, hip and knee replacements, exacerbations of COPD; heart bypass. The penalties were capped at 1% of Medicare reimbursements in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015. The government estimates that the penalties for fiscal year 2015 will total $424 million and affect 2,638 hospitals, representing an average penalty of more than $160,000 per hospital. Nearly 20% older adults are readmitted to a hospital within 30 days of discharge. Given that more than half of these readmissions are preventable, the new penalties are compelling hospitals to make the reduction of readmissions a priority. The community liaison pharmacist provides the missing link between hospital care and the home, as well as among different health care providers, thereby minimizing admission to the hospital due to medication mismanagement and promoting appropriate allocation of health care resources. And community pharmacists, the health care professionals who have the most interaction with patients’ post-discharge, are often underutilized. Being an integral part of the transition-of-care process, pharmacists can not only show their value but move the pharmacy profession toward being recognized as comprising health care providers. Community liaison programs clearly help reduce hospital readmissions and other types of harm and wasted resources associated with preventable adverse drug events (Kripalani et.al., 2012; Garza, 2017; Dowel, 2013; Grissinger, 2015).

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

The Future Home Care

Shocking as it sounds, 50 million Americans will be 65 years old or older by 2020, representing 17% of the population (Stover, 2018). More than 70% of patients of the Mobility Clinic reported improved access to care when their condition worsened (Lofters et.al., 2016). Nearly one-third of older home health care patients have a potential medication problem or are taking a drug considered inappropriate for older people (Ellenbecker et.al., 2008). The demand for informal caregivers is expected to rise by more than 85% over the next few decades due to the growing population of older adults, many of whom will experience significant functional impairment related to chronic illness (Sautter et.al., 2014). Over 30% of the patients requiring in-home care are either disabled or suffering from a chronic health condition that requires patient aid. Many home healthcare services often refuse new patients only due to lack of sufficient staff (Bradley et.al., 2015). HH (home health) care agencies serving 3.4 million Medicare beneficiaries at a cost of 17.9 billion U.S. dollars (Irani et.al., 2018). It is estimated that, of the 38.2 million adults age 65 and older in the United States, more than a quarter (29%) receive assistance for health or functioning reasons. The burdens of caregiving include physical, psychological, and financial hardships, and can have serious consequences for caregivers’ overall health, immune functioning, and longevity (Riffin et.al., 2017). All these practical situations clearly define the scope and features of future home health skilled medicare which is paid for under the Medicare home health benefit and delivered by Medicare-certified home health agencies. Home health care is one type of home-based care. A subset of home health providers is already developing these capabilities and can be seen as harbingers of the future for how home health providers may ultimately progress and experience risk-based payments. Many of the providers focusing on specific clinical conditions, most often chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), and diabetes. Medicare officials have already signaled their willingness to enable some flexibility in new payment models when providers have a financial stake in their performance against quality and cost targets; however, current challenges and structures do not allow home health care to be used optimally (landers et.al., 2016).

Figure 9. Framework for home health of the future. Home health agencies of the future must provide care that is: (1) Patient and person centered (2) Seamlessly connected and coordinated (3) High quality (4) Technology enabled. Three critical roles for the home health agency of the future (1) Post–acute care and acute care support (2) Primary care partners (3) Home-based long-term care partners. The home health agency of the future increasingly has new payment incentives and shared savings contracts for per - forming these roles capably and efficiently. In many instances, the home health agency of the future is structurally and formally more connected (as the owners, partners, or subsidiaries) of entities that integrate a range of home-based services beyond home health agency care (Landers et.al., 2016).

CONCLUSION

Community pharmacists are among the most accessible front-line primary care practitioners and are well positioned to affect the care of homebound patients. Pharmacist-directed home medication reviews offer an effective mechanism to address the pharmacotherapy issues of those members of the community who are most in need but may otherwise lack access to pharmacy services. As the general population ages, the demand for such services will undoubtedly increase. Pharmacist-directed home medication reviews could serve to minimize inappropriate use of medication, maximize health care cost savings and expand the scope of pharmacy practice.

REFERENCES

1. Aydede SK, Komenda P, Djurdjev O, Levin A. (2014); Chronic kidney disease and support provided by home care services: a systematic review; BMC Nephrol; 15; 118.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) (2002); ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in hospice and palliative care; Am J Health Syst Pharm. ; 59(18);1770-3

3. Anderson SL, Marrs JC. (2018); A Review of the Role of the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Transition of Care; Adv Ther; 35(3); 311-323.

4. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. (2018); Effect of a Program Combining Transitional Care and Long-term Self-management Support on Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial; JAMA; 320(22); 2335–2343

5. Atayee RS, Sam AM, Edmonds KP. (2018); Patterns of Palliative Care Pharmacist Interventions and Outcomes as Part of Inpatient Palliative Care Consult Service; J Palliat Med; Dec;21(12); 1761-1767

6. Bainbridge D, Brazil K, Krueger P, Ploeg J, Taniguchi A. (2010); A proposed systems approach to the evaluation of integrated palliative care. BMC Palliat Care; 9;8

7. Boylan P, Joseph T, Hale G, Moreau C, Seamon M, Jones R. (2018); Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Heart Failure Self-Management Kits for Outpatient Transitions of Care; Consult Pharm; 33(3);152-158.

8. Boyle J, Speroff T, Katherine Worley, MLIS, Aize Cao, PhD, Goggins K, Dittus RS, Kripalani S, (2017); Low Health Literacy Is Associated with Increased Transitional Care Needs in Hospitalized Patients; J. Hosp. Med; 12(11); 918-924

9. Batey C. (2016); The Pharmacist’s Role in Care for Elective Total Hip Arthroplasty/ Total Knee Arthroplasty; Transitions of Care America’s Pharmacist; 32-34

10. Bowman B, Zheng S, Yang A, Schiller B, Morfín JA, Seek M, Lockridge RS. (2018); Improving Incident ESRD Care Via a Transitional Care Unit; Am J Kidney Dis; 72(2); 278-283

11. Bradley S, Kamwendo F, Chipeta E, Chimwaza W, de Pinho H, McAuliffe E. (2015); Too few staff, too many patients: a qualitative study of the impact on obstetric care providers and on quality of care in Malawi; BMC Pregnancy Childbirth; 15;65

12. Chen T.F. (2016); Pharmacist-led Home Medicines Review and Residential Medication Management Review: The Australian model; Drugs Aging; 33(3); 199–204

13. Cascini S, Agabiti N, Incalzi RA, et al. (2013); Pneumonia burden in elderly patients: a classification algorithm using administrative data; BMC Infect Dis; 13:559.

14. CAPC Press Release. Palliative Care Continues Its Annual Growth Trend, According to Latest Center to Advance Palliative Care Analysis. February 28, 2018

15. Clark K, Smith JM, Currow DC. (2012); The prevalence of bowel problems reported in a palliative care population. J Pain Symptom Manage; 43(6); 993-1000

16. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, Niesner KJ, Schnipper JL, Kripalani S. (2012); Improving care transitions: the patient perspective; J Health Commun; Suppl 3:312-24

17. Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA. (2010); Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr Med Chem.; 17(6);571-84

18. Davison CM, Kahwa E, Atkinson U, Hepburn-Brown C, Aiken J, Dawkins P, Rae T, Edwards N, Roelofs S, MacFarlane D. (2013); Ethical challenges and opportunities for nurses in HIV and AIDS community-based participatory research in Jamaica. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics; 8(1); 55-67

19. Dowel G. (2013); Pharmacists can help reduce avoidable hospital admissions in the community; The Pharmaceutical Journal

20. Deeks L.S., Cooper G.M., Draper B., Kurrle S., Gibson D.M. (2016); Dementia, medication and transitions of care; Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm; 12(3); 450-60

21. Demler TL. (2016); Pharmacist Involvement in Hospice and Palliative Care. U.S. Pharmacist®

22. Del Fabbro E. Palliative care: assessment and management of nausea and vomiting. UpToDate website. uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-assessment-and-management-of-nausea-and-vomiting. Accessed August 23, 2016

23. DelBoccio S, DelBoccio S, Smith DF, Hicks M, Voight Lowe P, Graves-Rust JE, Volland J, Fryda S. (2015); Successes and Challenges in Patient Care Transition Programming: One Hospital's Journey; Online J Issues Nurs ;20(3):; 2

24. Devik SA, Olsen RM, Fiskvik IL, Halbostad T, Lassen T, Kuzina N, Enmarker I. (2018); Variations in drug-related problems detected by multidisciplinary teams in Norwegian nursing homes and home nursing care; Scand J Prim Health Care; 36(3); 291-299

25. Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. (2005); A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med; 20(10); 953-7.

26. Ellenbecker CH, Samia L, Cushman MJ, et al. (2008); Patient Safety and Quality in Home Health Care. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 13.

27. Erichsén E, Milberg A, Jaarsma T, Friedrichsen MJ. (2015); Constipation in specialized palliative care: prevalence, definition, and patient-perceived symptom distress. J Palliat Med; 18(7); 585-592.

28. Farris KB, Carter BL, Xu Y, et al. (2014); Effect of a care transition intervention by pharmacists: an RCT; BMC Health Serv Res; 14; 406.

29. Fernandez E, Perez R, Hernandez A, Tejada P, Arteta M, Ramos JT. (2011); Factors and Mechanisms for Pharmacokinetic Differences between Pediatric Population and Adults. Pharmaceutics; 3(1); 53-72

30. Flanagan PS, Barns A. (2018); Current perspectives on pharmacist home visits: do we keep reinventing the wheel? ; Integrated Pharmacy Research and Practice; 7; 141–159.

31. Ferrah N, Lovell JJ, Ibrahim JE. (2017); Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Medication Errors Resulting in Hospitalization and Death of Nursing Home Residents. J Am Geriatr Soc; 65(2); 433-442.

32. Gray A. (2015); Refer-To-Pharmacy: Pharmacy for the Next Generation Now! A Short Communication for Pharmacy; Pharmacy (Basel); 3(4);364-371.

33. Garza A. (2017); Transition of Care: An Opportunity for Community Pharmacists; PharmacyTimes

34. Grissinger M. (2015); Reduce readmissions with pharmacy programs that focus on transitions from the hospital to the community; P T; 40(4); 232-3.

35. Glare P, Miller J, Nikolova T, Tikoo R. (2011); Treating nausea and vomiting in palliative care: a review; Clin Interv Aging ;6:243-259

36. Gonçalves F. (2018); Deprescription in Advanced Cancer Patients.; Pharmacy (Basel).;6(3); 88.

37. Grönheit W, Popkirov S, Wehner T, Schlegel U, Wellmer J. (2018); Practical Management of Epileptic Seizures and Status Epilepticus in Adult Palliative Care Patients. Front Neurol; 9; 595

38. Goodman M, Low J, Wilkinson S. (2005); Constipation management in palliative care: a survey of practices in the United Kingdom. J Pain Symptom Manage; 29(3); 238-244

39. Haggan M. Palliative care: Pharmacist breaks down roadblocks. AJP.com.au News 26/05/2017.

40. Hofmeister M, Memedovich A, Dowsett LE, et al. (2018); Palliative care in the home: a scoping review of study quality, primary outcomes, and thematic component analysis. ; BMC Palliat Care; 17(1);41

41. Irani E, Hirschman KB, Cacchione PZ, Bowles KH. (2018); Home health nurse decision-making regarding visit intensity planning for newly admitted patients: a qualitative descriptive study; Home Health Care Serv Q; 37(3);211-231

42. Jordan M, Keefer PM, Lee YA, Meade K, Snaman JM, Wolfe J, Kamal A, Rosenberg A. (2018); Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Caring for Children. J Palliat Med; 21(12); 1783-1789

43. Kristeller J. (2014); Transition of care: pharmacist help needed; Hosp Pharm; 49(3); 215-6.

44. Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dalal AK, et al. (2012); Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. ; 157(1); 1-10.

45. Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B, Rosati RJ, McCann BA, Hornbake R, MacMillan R, Jones K, Bowles K, Dowding D, Lee T, Moorhead T, Rodriguez S, Breese E. (2016); The Future of Home Health Care: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Value.; Home Health Care Manag Pract; 28(4);262-278

46. Lofters A, Guilcher S, Maulkhan N, Milligan J, Lee J. (2016); Patients living with disabilities: The need for high-quality primary care. Can Fam Physician; 62(8):e457-64.

47. Louis AJ, Arora VM, Matthiesen MI, Meltzer DO, Press VG. (2016); Screening Hospitalized Patients for Low Health Literacy: Beyond the REALM of Possibility?; Health Educ Behav; 44(3); 360-364.

48. Lee HR, Yi SY, Kim DY. (2013); Evaluation of Prescribing Medications for Terminal Cancer Patients near Death: Essential or Futile. Cancer Res Treat; 45(3); 220-5.

49. Mason V. (2016); Pharmacist House Calls Improve Health of Virginia Mason Heart Failure Patients. News Release

50. Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JA. (2016); Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis; BMJ Open. ;6(2):e010003

51. Manabe T, Teramoto S, Tamiya N, Okochi J, Hizawa N. (2015); Risk Factors for Aspiration Pneumonia in Older Adults; PLoS One; 10(10); e0140060.

52. Medscape Pharmacists (2007); Methadone, Pain Management, and Palliative Care. Available From: https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/550895

53. McDerby N, Naunton M, Shield A, Bail K, Kosari S. (2018); Feasibility of Integrating Residential Care Pharmacists into Aged Care Homes to Improve Quality Use of Medicines: Study Protocol for a Non-Randomised Controlled Pilot Trial; Int J Environ Res Public Health;15(3); 499

54. Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. (2014); Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications; Br J Clin Pharmacol; 57(1); 6-14.

55. Masman AD, van Dijk M, Tibboel D, Baar FP, Mathôt RA. (2015); Medication use during end-of-life care in a palliative care centre. Int J Clin Pharm; 37(5); 767-775

56. Mansukhani RP, Bridgeman MB, Candelario D, Eckert LJ. (2015); Exploring Transitional Care: Evidence-Based Strategies for Improving Provider Communication and Reducing Readmissions; P T; 40(10); 690-4.

57. Mohiuddin AK. (2019); Community and Clinical Pharmacists in Transition Care; Glob J Pharmacia Sci; 7(2); 555706.

58. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Standards of Practice for Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice. Available From: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/quality/Ped_Pall_Care%20_Standard.pdf.pdf

59. Nguyen TS, Nguyen TLH, Van Pham TT, Hua S, Ngo QC, Li SC. (2018); Pharmacists' training to improve inhaler technique of patients with COPD in Vietnam; Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis; 13; 1863-1872

60. NHS England. Medicines optimisation in care homes. Available From: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/primary-care/pharmacy/medicines-optimisation-in-care-homes/

61. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2013); NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): palliative care

62. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (NCC-C, UK), Cardiff. (2012); Opioids in palliative care: safe and effective prescribing of strong opioids for pain in palliative care of adults

63. Patton AP, Liu Y, Hartwig DM, May JR, Moon J, Stoner SC, Guthrie KD. (2017); Community pharmacy transition of care services and rural hospital readmissions: A case study; J Am Pharm Assoc (2003); 57(3S); S252-S258.e3

64. Patel A, Dunmore-Griffith J, Lutz S, Johnstone PA. (2013); Radiation therapy in the last month of life; Rep Pract Oncol Radiother; 19(3); 191-4

65. Rak A, Raina R, Suh TT, Krishnappa V, Darusz J, Sidoti CW, Gupta M. (2017); Palliative care for patients with end-stage renal disease: approach to treatment that aims to improve quality of life and relieve suffering for patients (and families) with chronic illnesses. Clin Kidney J; 10(1); 68-73.

66. Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL, Fried T. (2017); Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers and Older Adults with and without Dementia and Disability; J Am Geriatr Soc; 65(8); 1821-1828.

67. Rinne ST, Lindenauer PK, Au DH. (2018); Intensive Intervention to Improve Outcomes for Patients With COPD; JAMA; 320(22); 2322–2324

68. Rydeman, Ingbritt. “Discharged From Hospital And In Need Of Home Care Nursing – Experience Of Older Persons , Their Relatives And Care Professionals.” (2012).

69. Rose L, Istanboulian L, Carriere L and others. (2018); Program of Integrated Care for Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Multiple Comorbidities (PIC COPD+): a randomised controlled trial; European Respiratory Journal; 51(1) 1701567

70. Rowlands G, Protheroe J, Winkley J, Richardson M, Seed PT, Rudd R. (2015); A mismatch between population health literacy and the complexity of health information: an observational study; Br J Gen Pract; 65(635);e379-86.

71. Pai AB, Cardone KE, Manley HJ, St Peter WL, Shaffer R, Somers M, Mehrotra R; (2013); Dialysis Advisory Group of American Society of Nephrology. Medication reconciliation and therapy management in dialysis-dependent patients: need for a systematic approach; Clin J Am Soc Nephrol; 8(11); 1988-99

72. Payne R.A., Abel G.A., Avery A.J., Mercer S.W., Roland M.O. (2014); Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary care; Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol; 77(6); 1073–1082

73. Sautter JM, Tulsky JA, Johnson KS, Olsen MK, Burton-Chase AM, Lindquist JH, Zimmerman S, Steinhauser KE. (2014); Caregiver experience during advanced chronic illness and last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc; 62(6); 1082-90.

74. Setter SM, Corbett CF, Neumiller JJ. (2012); Transitional care: exploring the home healthcare nurse's role in medication management; Home healthcare nurse; 30(1); 19-26

75. Shannon R, Jenifer M, Tom L, Mary Ann B. (2013); The Role of a Pharmacist on the Home Care Team: A Collaborative Model Between a College of Pharmacy and a Visiting Nurse Agency; Home Healthcare ; 31(2); 80-7

76. Sugathan S, Singh D and others. (2014); Reported Prevalence And Risk Factors Of Chronic Non Communicable Diseases Among Inmates Of Old-Age Homes In Ipoh, Malaysia; International Journal of Preventive and Therapeutic Medicine; 2(4); OCT-DEC

77. Simonetti AF, Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Carratalà J. (2014); Management of community-acquired pneumonia in older adults; Ther Adv Infect Dis; 2(1); 3-16.

78. Sen S, Bowen JF, Ganetsky VS, Hadley D, Melody K, Otsuka S, Vanmali R, Thomas T. (2014); Pharmacists implementing transitions of care in inpatient, ambulatory and community practice settings. Pharm Pract (Granada) ;12(2); 439

79. Stevenson S. (2017); The 5 Most Common Infections in the Elderly. A Place For Mom Posted.

80. Stover M. (2018); How Technology Solutions Are Shaping The Future Of Home Healthcare; Web healthworkscollective.com

81. Tait P, Morris B, To T. (2014); Core palliative medicines Meeting the needs of non-complex community patients; Australian Family Physician; 43(1); 29-32

82. Trang J, Martinez A, Aslam S, Duong MT. (2015); Pharmacist Advancement of Transitions of Care to Home (PATCH) Service; Hosp Pharm; 50(11); 994-1002.

83. Tong E.Y., Roman C.P., Mitra B., Yip G.S., Gibbs H., Newnham H.H., Smit D.V., Galbraith K., Dooley M.J. (2017); Reducing medication errors in hospital discharge summaries: A randomised controlled trial; Med. J. Aust; 206(1);36-39

84. Tonkin-Crine S, Okamoto I, Leydon GM, Murtagh FE, Farrington K, Caskey F, Rayner H, Roderick P. (2015); Understanding by older patients of dialysis and conservative management for chronic kidney failure; Am J Kidney Dis; 65(3);443-50

85. van der Molen T, van Boven JF, Maguire T, Goyal P, Altman P. (2016); Optimizing identification and management of COPD patients - reviewing the role of the community pharmacist; Br J Clin Pharmacol; 83(1);192-201.

86. Wei X, Ma Z, Yu N, et al. (2017); Risk factors predict frequent hospitalization in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD; Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis; 13; 121-129

87. Walus AN, Woloschuk DMM. (2017); Impact of Pharmacists in a Community-Based Home Care Service: A Pilot Program. Can J Hosp Pharm; 70(6); 435-442.

88. Wolstenholme B. (2011); Medication-Related Problems in Geriatric Pharmacology; Aging Well Summer; 4(3); 8

89. Walker KA, Scarpaci L, McPherson ML. (2010); Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist; Am J Hosp Palliat Med; 27(8); 511-513

90. Wilson DM, Cohen J, Deliens L, Hewitt JA, Houttekier D. (2013); The preferred place of last days: results of a representative population-based public survey. J Palliat Med.; 16; 502–508

91. Wick JY. (2015); Pharmacist Home Visits Improve Heart Failure Management. PharmacyTimes

92. Web Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). About Transitional Care. Available From: https://www.pcori.org/research-results/transitional-care/about-transitional-care

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE