{ DOWNLOAD AS PDF }

ABOUT AUHTORS

Priyanka R. Waghmare1*, Priynka G. Kakade1 , Prashant L. Takdhat2, Ashwini M. Nagrale2, SM Thakare2, MM Parate3

1 Dr. R. G. Bhoyar Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research,

Wardha, Maharashtra, India

2 Dr. R. G. Bhoyar Institute of Pharmacy,

Wardha, Maharashtra, India

3 Daga Memorial Hospital,

Maharashtra, Nagpur, India

*waghmarepriyancka@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Herbal medicines are gaining increased popularity due to their advantages, such as better patient tolerance, long history of use, fewer side-effects and being relatively less expensive. Furthermore, they have provided good evidence for the treatment of a wide variety of difficult to cure diseases. The skin is the outermost layer of the body that is often easily damaged by environmental factors as well as stress and poor eating habits. Acne vulgaris (or simply acne) is an infectious disease and one of the most prevalent human diseases. Acne is a cutaneous pleomorphic disorder of the pilosebaceous unit involving abnormalities in sebum production and is characterized by both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions. Common therapies that are used for the treatment of acne include topical, systemic, hormonal, herbal and combination therapy. Although here is a wide market for cosmetic products that offers to improve skin problems, nature also provides a solution to these. Although the medical and surgical treatment options are the same, it is these features that should be kept in mind when designing a treatment regimen for acne. Natural treatments for skin that give lasting results are often better than expensive commercial products and cosmetic procedures. One such natural treatment is turmeric powder for skin. Turmeric is considered safe in amounts found in foods and when taken orally and topically in medicinal quantities. Turmeric’s primary biologically active component is curcumin. Research has shown that curcumin has potent antioxidant, wound-healing, and anti-inflammatory properties, which may prove to be therapeutic against acne. This review focuses on the treatment of acne using turmeric as medicinal drug.

[adsense:336x280:8701650588]

REFERENCE ID: PHARMATUTOR-ART-2484

|

PharmaTutor (Print-ISSN: 2394 - 6679; e-ISSN: 2347 - 7881) Volume 5, Issue 4 Received On: 31/12/2017; Accepted On: 10/01/2017; Published On: 01/04/2017 How to cite this article: Waghmare PR, Kakade PG, Takdhat PL, Nagrale AM, Thakare SM, Parate MM;Turmeric as Medicinal Plant for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris; PharmaTutor; 2017; 5(4); 19-27 |

INTRODUCTION

The skin is the outermost layer of the body that is often easily damaged by environmental factors as well as stress and poor eating habits. Although here is a wide market for cosmetic products that offers to improve skin problems, nature also provides a solution to these. Acne vulgaris (or simply acne) is an infectious disease and one of the most prevalent human diseases. It is characterized by different areas of scaly red skin (seborrhea), pinheads (papules), blackheads and whiteheads (comedones), large papules (nodules), and sometimes scarring (piples). Severe acne is usually inflammatory, however it may also be non-inflammatory. In acne, the skin changes, due to changes in pilosebaceous unit skin structures including hair follicles and their associated sebaceous glands. These changes usually require androgen stimulation (1). Acne vulgaris is usually due to an increase in body androgens, and occurs more often in adolescence during puberty. Acne is usually seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and the back of subjects who possess greater numbers of oil glands (2). Natural treatments for skin that give lasting results are often better than expensive commercial products and cosmetic procedures. One such natural treatment is turmeric powder for skin.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa): Turmeric’s primary biologically active component is curcumin. Research has shown that curcumin has potent antioxidant, wound-healing, and anti-inflammatory properties, which may prove to be therapeutic against acne. Turmeric is considered safe in amounts found in foods and when taken orally and topically in medicinal quantities. It may cause atopic dermatitis in some people. However, pregnant women should not take medicinal amounts of turmeric because it could stimulate the uterus.36Topically turmeric may cause the skin to temporarily stain yellow-especially in people with light skin tones. When used as a topical remedy, it is typically mixed with water or honey to a pasty consistency and applied directly to the skin. Orally, dried turmeric can be mixed into liquid and consumed.

Kingdom Plantae

Genus : Curcuma

Species : C. longa

Binomial name: Curcuma longa

Common Names : Kunyit, Haridra, Haldi, Indian Saffron, and Arishina

Indian Names : Haldi (Hindi), Pasupu (Telugu), Manjal (Tamil), Manjal (Malayalam), Arasina (Kananda), Haldar (Gujarati), Halud (Bengali) and Halad (Marathi)

Definition

Rhizoma Curcumae Longae is the dried rhizome of Curcuma longa L. (Zingiberaceae) (1).

Synonyms

Kunyit, Haridra, Haldi, Indian Saffron, and Arishina

Selected vernacular names

Acafrao, arqussofar, asabi-e-safr, avea, cago rerega, chiang-huang, common tumeric, curcum, curcuma, dilau, dilaw, Gelbwurzel, gezo, goeratji, haladi, haldi, haldu, haku halu, hardi, haridra, huang chiang, hsanwen, hurid, Indian saffron, jiânghuang, kaha, kakoenji, kalo haledo, khamin chan, khaminchan, kilunga kuku, kitambwe, kiko eea, koening, koenit, koenjet, kondin, kooneit, kunyit, kurcum, kurkum, Kurkumawurzelstock, luyang dilaw, mandano, manjano, manjal, nghe, nisha, oendre, pasupu, rajani, rame, renga, rhizome de curcuma, saffran vert, safran, safran des indes, skyer-rtsa, tumeric, tumeric root, tumeric rhizome, turmeric, yellow root, zardchob (1–3, 6–14).

Description

Perennial herb up to 1.0 m in height; stout, fleshy, main rhizome nearly ovoid (about 3 cm in diameter and 4 cm long). Lateral rhizome, slightly bent (1cm × 2–6cm), flesh orange in colour; large leaves lanceolate, uniformly green, up to 50cm long and 7–25cm wide; apex acute and caudate with tapering base, petiole and sheath sparsely to densely pubescent. Spike, apical, cylindrical, 10– 15cm long and 5–7 cm in diameter. Bract white or white with light green upper half, 5–6 cm long, each subtending flowers, bracteoles up to 3.5 cm long. Pale yellow flowers about 5cm long; calyx tubular, unilaterally split, unequally toothed; corolla white, tube funnel shaped, limb 3-lobed. Stamens lateral, petaloid, widely elliptical, longer than the anther; filament united to anther about the middle of the pollen sac, spurred at base. Ovary trilocular; style glabrous. Capsule ellipsoid. Rhizomes orange within (1, 4, 6, 15).

Plant material of interest: dried rhizome

General appearance

The primary rhizome is ovate, oblong or pear-shaped round turmeric, while the secondary rhizome is often short-branched long turmeric; the round form is about half as broad as long; the long form is from 2–5cm long and 1–1.8cm thick; externally yellowish to yellowish brown, with root scars and annulations, the latter from the scars of leaf bases; fracture horny; internally orange yellow to orange; waxy, showing a cortex separated from a central cylinder by a distinct endodermis (1, 9, 13).

Organoleptic properties

Odour, aromatic; taste, warmly aromatic and bitter (1, 9, 13). Drug when chewed colours the saliva yellow (9).

Microscopic characteristics

The transverse section of the rhizome is characterized by the presence of mostly thin-walled rounded parenchyma cells, scattered vascular bundles, definite endodermis, a few layers of cork developed under the epidermis and scattered oleoresin cells with brownish contents. The cells of the ground tissue are also filled with many starch grains. Epidermis is thin walled, consisting of cubical cells of various dimensions. The cork cambium is developed from the subepidermal layers and even after the development of the cork, the epidermis is retained. Cork is generally composed of 4–6 layers of thin-walled brick shaped parenchymatous cells. The parenchyma of the pith and cortex contains curcumin and is filled with starch grains. Cortical vascular bundles are scattered and are of collateral type. The vascular bundles in the pith region are mostly scattered and they form discontinuous rings just under the endodermis. The vessels have mainly spiral thickening and only a few have reticulate and annular structure (1, 8, 9).

Powdered plant material

Coloured deep yellow. Fragments of parenchymatous cells contain numerous altered, pasty masses of starch grains coloured yellow by curcumin, fragments of vessels; cork fragments of cells in sectional view; scattered unicellular trichomes; abundant starch grains; fragments of epidermal and cork cells in surface view; and scattered oil droplets, rarely seen (1, 13).

Geographical distribution

Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Madagascar, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam (1, 13, 16). It is extensively cultivated in China, India, Indonesia, Thailand and throughout the tropics, including tropical regions of Africa (1, 7, 13, 16)

Methodology

General identity tests

Macroscopic and microscopic examinations; test for the presence of curcuminoids by colorimetric and thin-layer chromatographic methods (1).

Purity tests

Microbiology

The test for Salmonella spp. in Rhizoma Curcumae Longae products should be negative. The maximum acceptable limits of other microorganisms are as follows (17–19). For preparation of decoction: aerobic bacteria-not more than 107/g; fungi-not more than 105/g; Escherichia coli-not more than 102/g. Preparations for internal use: aerobic bacteria-not more than 105/g or ml; fungi-not more than 104/g or ml; enterobacteria and certain Gram-negative bacteria-not more than 103/g or ml; Escherichia coli-0/g or ml.

Foreign organic matter

Not more than 2% (1, 9).

Total ash

Not more than 8.0% (1, 15).

Acid-insoluble ash

Not more than 1% (1, 9, 15).

Water-soluble extractive

Not less than 9.0% (1).

Alcohol-soluble extractive

Not less than 10% (1).

Moisture

Not more than 10% (1).

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Pesticide residues

To be established in accordance with national requirements. Normally, the maximum residue limit of aldrin and dieldrin in Rhizoma Curcumae Longae is not more than 0.05 mg/kg (19). For other pesticides, see WHO guidelines on quality control methods for medicinal plants (17) and guidelines for predicting dietary intake of pesticide residues (20).

Heavy metals

Recommended lead and cadmium levels are not more than 10 and 0.3mg/kg, respectively, in the final dosage form of the plant material (17).

Radioactive residues

For analysis of strontium-90, iodine-131, caesium-134, caesium-137, and plutonium-239, see WHO guidelines on quality control methods for medicinal plants (17).

Other purity tests

Chemical tests to be established in accordance with national requirements.

Chemical assays

Not less than 4.0% of volatile oil, and not less than 3.0% of curcuminoids (1). Qualitative analysis by thin-layer and high-performance liquid chromatography (1, 21) and quantitative assay for total curcuminoids by spectrophotometric (1, 22) or by high-performance liquid chromatographic methods (23, 24).

Major chemical constituents

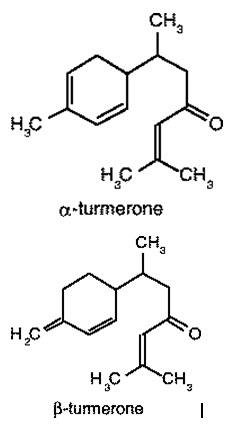

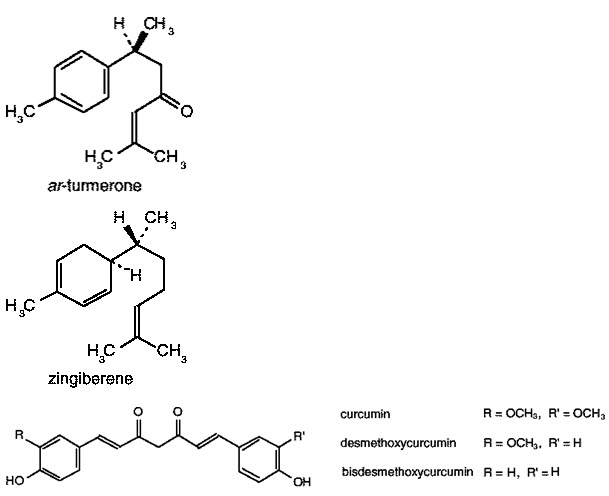

Pale yellow to orange-yellow volatile oil (6%) composed of a number of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, including zingiberene, curcumene, α- and β- turmerone among others. The colouring principles (5%) are curcuminoids, 50–60% of which are a mixture of curcumin, monodesmethoxycurcumin and bisdesmethoxycurcumin (1, 6, 25). Representative structures of curcuminoids are presented below.

Dosage forms

Powdered crude plant material, rhizomes (1, 2), and corresponding preparations (25). Store in a dry environment protected from light. Air dry the crude drug every 2–3 months (1).

Medicinal uses

Uses supported by clinical data

The principal use of Rhizoma Curcumae Longae is for the treatment of acid, flatulent, or atonic dyspepsia (26–28).

Uses described in pharmacopoeias and in traditional systems of medicine

Treatment of peptic ulcers, and pain and inflammation due to rheumatoid arthritis (2, 11, 14, 29, 30) and of amenorrhoea, dysmenorrhoea, diarrhoea, epilepsy, pain, and skin diseases (2, 3, 16).

Uses described in folk medicine, not supported by experimental or clinical data

The treatment of asthma, boils, bruises, coughs, dizziness, epilepsy, haemorrhages, insect bites, jaundice, ringworm, urinary calculi, and slow lactation (3, 7, 8–10, 14).

Pharmacology

Experimental pharmacology

Anti-inflammatory activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of Rhizoma Curcumae Longae has been demonstrated in animal models (3, 30–32). Intraperitoneal administration of the drug in rats effectively reduced both acute and chronic inflammation in carrageenin induced paw oedema, the granuloma pouch test, and the cotton pellet granuloma test (32, 33). The effectiveness of the drug in rats was reported to be similar to that of hydrocortisone acetate or indometacin in experimentally induced inflammation (31, 32). Oral administration of turmeric juice or powder did not produce an anti-inflammatory effect; only intraperitoneal injection was effective (33). The volatile oil has exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in rats against adjuvant-induced arthritis, carrageenin induced paw oedema, and hyaluronidase-induced inflammation (32). The anti-inflammatory activity appears to be mediated through the inhibition of the enzymes trypsin and hyaluronidase (33). Curcumin and its derivatives are the active anti-inflammatory constituents of the drug (34 –40). After intraperitoneal administration, curcumin and sodium curcuminate exhibited strong anti-inflammatory activity in the carrageenin-induced oedema test in rats and mice (41). Curcumin was also found to be effective after oral administration in the acute carrageenin-induced oedema test in mice and rats (41). The anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin may be due to its ability to scavenge oxygen radicals, which have been implicated in the inflammation process (42). Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of a polysaccharide fraction, isolated from the drug, increased phagocytosis capacity in mice in the clearance of colloidal carbon test (43).

Activity against peptic ulcer and dyspepsia

Oral administration to rabbits of water or methanol extracts of the drug signifi- cantly decreased gastric secretion (44) and increased the mucin contents of gastric juice (45). Intragastric administration of an ethanol extract of the drug to rats effectively inhibited gastric secretion and protected the gastroduodenal mucosa against injuries caused by pyloric ligation, hypothermic-restraint stress, indometacin, reserpine, and mercaptamine administration, and cytodestructive agents such as 80% methanol, 0.6mol/l hydrochloric acid, 0.2mol/l sodium hydroxide and 25% sodium chloride (30, 46). The drug stimulated the production of gastric wall mucus, and it restored non-protein sulfides in rats (46, 47). Curcumin, one of the anti-inflammatory constituents of the drug, has been shown to prevent and ameliorate experimentally induced gastric lesions in animal models by stimulation of mucin production (48). However, there are conflicting reports regarding the protective action of curcumin against histamine-induced gastric ulceration in guinea-pigs (41). Moreover, both intraperitoneal and oral administration of curcumin (100 mg/kg) have been reported to induce gastric ulceration in rats (41, 49–51).

Non-specific inhibition of smooth muscle contractions in isolated guinea-pig ileum by sodium curcuminate has been reported (41).

The effect of curcumin on intestinal gas formation has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. Addition of curcumin to Clostridium perfringens of intestinal origin in vitro and to a chickpea flour diet fed to rats led to a gradual reduction in gas formation (41).

Both the essential oil and sodium curcuminate increase bile secretion after intravenous administration to dogs (41). In addition, gall-bladder muscles were stimulated (39).

Clinical pharmacology

Oral administration of the drug to 116 patients with acid dyspepsia, flatulent dyspepsia, or atonic dyspepsia in a randomized, double-blind study resulted in a statistically significant response in the patients receiving the drug (27). The patients received 500 mg of the powdered drug four times daily for 7 days (27). Two other clinical trials which measured the effect of the drug on peptic ulcers showed that oral administration of the drug promoted ulcer healing and decreased the abdominal pain involved (28, 29).

Two clinical studies have shown that curcumin is an effective antiinflammatory drug (52, 53). A short-term (2 weeks) double-blind, crossover study of 18 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed that patients receiving either curcumin (1200 mg/day) or phenylbutazone (30 mg/day) had significant improvement in morning stiffness, walking time and joint swelling (52). In the second study, the effectiveness of curcumin and phenylbutazone on postoperative inflammation was investigated in a double-blind study (53). Both drugs produced a better anti-inflammatory response than a placebo (53), but the degree of inflammation in the patients varied greatly and was not evenly distributed among the three groups.

Contraindications

Obstruction of the biliary tract. In cases of gallstones, use only after consultation with a physician (26). Hypersensitivity to the drug.

Warnings

No information available.

Precautions

Carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, impairment of fertility

Rhizoma Curcumae Longae is not mutagenic in vitro (54–56).

Pregnancy: teratogenic effects

Orally administered Rhizoma Curcumae Longae was not tetratogenic in mice or rats (34, 57, 58).

Pregnancy: non-teratogenic effects

The safety of Rhizoma Curcumae Longae during pregnancy has not been established. As a precautionary measure the drug should not be used during pregnancy except on medical advice (59).

Nursing mothers

Excretion of the drug into breast milk and its effects on the newborn have not been established. Until such data are available, the drug should not be used during lactation except on medical advice.

Paediatric use

The safety and effectiveness of the drug in children has not been established.

Other precautions

No information on drug interactions or drug and laboratory test interactions was found.

Adverse reactions

Allergic dermatitis has been reported (60). Reactions to patch testing occurred most commonly in persons who were regularly exposed to the substance or who already had dermatitis of the finger tips. Persons who were not previously exposed to the drug had few allergic reactions (60).

Posology

Crude plant material, 3–9g daily (5, 6); powdered plant material, 1.5–3.0 g daily (9, 19); oral infusion, 0.5–1g three times per day; tincture (1: 10) 0.5–1ml three times per day.

Results:

Consumption of alternative and complementary medicine, including medicinal plants, is increasing and is common amongst patients affected by acne and infectious skin diseases. Medicinal plants have a long history of use and have been shown to possess low side effects. These plants are a reliable source for preparation of new drugs.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Conclusions:

Many plants seem to have inhibitory effects on the growth of bacteria, fungi and viruses in vitro. Also, some plants have been shown to have anti-inflammatory and anti-fat properties. However, there are a few evidences about the effectiveness and safety of these plants in the treatment of acne and other skin infections. For this reason, chemical drugs seem to still be the first choice in the treatment of acne and skin infections. However, the efficacy and safety of synthetic drugs are under question in the treatment of acne and other skin infections. Plant reviewed in this paper have shown promising results. Hence, they might possibly be used alone or as adjuvant with other therapeutic measures or in mild to moderate situations. Possible contact sensitization especially in topical or oral use should be considered. Further clinical studies validated with controls are required to use plant particularly the species of turmeric to treat acne. Efficacy and clinical safety trials are also essential in bacterial skin infections. Mechanism of action of these plants is another important subject, which should be addressed. Phenolic compounds derived from plants have been shown to possess antibacterial activity. Most of the presented plant species in this review article possess these compounds. However, in most cases it is not known how much these compounds are responsible for their anti-acne activity. It should be noted that a lot of other plants have phenolic compounds (61, 62, 63-73). Hence, if these compounds are solely responsible for the observed anti-acne activities, all plants with phenolic compounds should have anti-acne properties, which worth examining.

References

1. Standard of ASEAN herbal medicine, Vol. 1. Jakarta, ASEAN Countries, 1993.

2. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China (English ed.). Guangzhou, Guangdong Science and Technology Press, 1992.

3. Chang HM, But PPH, eds. Pharmacology and applications of Chinese materia medica, Vol. 1. Singapore, World Scientific Publishing, 1986.

4. Keys JD. Chinese herbs, their botany, chemistry and pharmacodynamics. Rutland, VT, CE Tuttle, 1976.

5. Wren RC. Potter's new cyclopedia of botanical drugs and preparations. Saffron Walden, C.W. Daniel, 1988.

6. Bisset NG. Max Wichtl's herbal drugs & phytopharmaceuticals. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 1994.

7. Ghazanfar SA. Handbook of Arabian medicinal plants. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 1994.

8. Kapoor LD. Handbook of Ayurvedic medicinal plants. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 1990.

9. The Indian pharmaceutical codex, Vol. I. Indigenous drugs. New Delhi, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, 1953.

10. Cambie RC, Ash J. Fijian medicinal plants. CSIRO, Australia, 1994.

11. Iwu MM. Handbook of African medicinal plants. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press, 1993.

12. Hsu HY. Oriental materia medica, a concise guide. Long Beach, CA, Oriental Healing Arts Institute, 1986.

13. Youngken HW. Textbook of pharmacognosy, 6th ed. Philadelphia, Blakiston, 1950.

14. Medicinal plants in Viet Nam. Manila, World Health Organization, 1990 (WHO Regional Publications, Western Pacific Series, No. 3).

15. Japanese standards for herbal medicines. Tokyo, Yakuji Nippon, 1993.

16. Medicinal plants in China. Manila, World Health Organization, 1989 (WHO Regional Publications, Western Pacific Series, No. 2).

17. Quality control methods for medicinal plant materials. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1998.

18. Deutsches Arzneibuch 1996. Vol. 2. Methoden der Biologie. Stuttgart, Deutscher Apotheker Verlag, 1996.

19. European pharmacopoeia, 3rd ed. Strasbourg, Council of Europe, 1997.

20. Guidelines for predicting dietary intake of pesticide residues, 2nd rev. ed. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997 (unpublished document WHO/FSF/FOS/97.7; available from Food Safety, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland).

21. Taylor SJ, McDowell IJ. Determination of curcuminoid pigments in turmeric (Curcuma domestica Val) by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Chromatographia, 1992, 34:73–77.

22. International Organization for Standardization. Turmeric-Determination of colouring power-Spectrophotometric method. ISO 5566, 1982.

23. König WA et al. Enantiomeric composition of the chiral constituents of essential oils. Part 2: Sesquiterpene hydrocarbon. Journal of high resolution chromatography, 1994, 17:315–320.

24. Zhao DY, Yang MK. Separation and determination of curcuminoids in Curcuma longa L. and its preparation by HPLC. Yao hsueh hsueh pao, 1986, 21:382–385.

25. Bruneton J. Pharmacognosy, phytochemistry, medicinal plants. Paris, Lavoisier, 1995.

26. German Commission E Monograph, Curcumae longae rhizoma. Bundesanzeiger, 1985, 223:30 November.

27. Thamlikitkul V et al. Randomized double blind study of Curcuma domestica Val. for dyspepsia. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 1989, 72:613–620.

28. Intanonta A et al. Treatment of abdominal pain with Curcuma longa L. (Report submitted to Primary Health Care Office, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, 1986.)

29. Prucksunand C et al. Effect of the long turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) on healing peptic ulcer: A preliminary report of 10 case studies. Thai journal of pharmacology, 1986, 8:139–151.

30. Masuda T et al. Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory curcumin-related phenolics from rhizomes of Curcuma domestica. Phytochemistry, 1993, 32:1557–1560.

31. Arora RB et al. Anti-inflammatory studies on Curcuma longa (turmeric). Indian journal of medical research, 1971, 59:1289–1295.

32. Yegnanarayan R, Saraf AP, Balwani JH. Comparison of antiinflammatory activity of various extracts of Curcuma longa (Linn). Indian journal of medical research, 1976, 64:601–608.

33. Permpiphat U et al. Pharmacological study of Curcuma longa. In: Proceedings of the Symposium of the Department of Medical Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, Dec 3–4, 1990.

34. Gupta SS, Chandra D, Mishra N. Anti-inflammatory and antihyaluronidase activity of volatile oil of Curcuma longa (Haldi). Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 1972, 16:254.

35. Chandra D, Gupta SS. Anti-inflammatory and antiarthritic activity of volatile oil of Curcuma longa. Indian journal of medical research, 1972, 60:138–142.

36. Tripathi RM, Gupta SS, Chandra D. Anti-trypsin and antihyaluronidase activity of volatile oil of Curcuma longa (Haldi). Indian journal of pharmacology, 1973, 5:260– 261.

37. Ghatak N, Basu N. Sodium curcuminate as an effective antiinflammatory agent. Indian journal of experimental biology, 1972, 10:235–236.

38. Srimal RC, Dhawan BN. Pharmacology of diferuloyl methane (curcumin), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent. Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology, 1973, 25:447–452.

39. Mukhopadhyay A et al. Antiinflammatory and irritant activities of curcumin analogs in rats. Agents and actions, 1982, 12:508–515.

40. Rao TS, Basu N, Siddiqui HH. Anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin analogs. Indian journal of medical research, 1982, 75:574–578.

41. Ammon HP, Wahl MA. Pharmacology of Curcuma longa. Planta medica, 1991, 57:1– 7.

42. Kunchandy E, Rao MN. Oxygen radical scavenging activity of curcumin. International journal of pharmacognosy, 1990, 58:237–240.

43. Kinoshita G, Nakamura F, Maruyama T. Immunological studies on polysaccharide fractions from crude drugs. Shoyakugaku zasshi, 1986, 40:325–332.

44. Sakai K et al. Effects of extracts of Zingiberaceae herbs on gastric secretion in rabbits. Chemical and pharmaceutical bulletin, 1989, 37:215–217.

45. Muderji B, Zaidi SH, Singh GB. Spices and gastric function. Part I. Effect of Curcuma longa on the gastric secretion in rabbits. Journal of scientific and industrial research, 1981, 20:25–28.

46. Rafatullah S et al. Evaluation of turmeric (Curcuma longa) for gastric and duodenal antiulcer activity in rats. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 1990, 29:25–34.

47. Bhatia A, Singh GB, Khanna NM. Effect of curcumin, its alkali salts and Curcuma longa oil on histamine-induced gastric ulceration. Indian journal of experimental biology, 1964, 2:158–160.

48. Sinha M et al. Study of the mechanism of action of curcumin: an antiulcer agent. Indian journal of pharmacy, 1975, 7:98–99.

49. Prasad DN et al. Studies on ulcerogenic activity of curcumin. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 1976, 20:92–93.

50. Gupta B et al. Mechanisms of curcumin induced gastric ulcers in rats. Indian journal of medical research, 1980, 71:806–814.

51. Srimal RC, Dhawan BN. In: Arora BA, ed. Development of Unani drugs from herbal sources and the role of elements in their mechanism of action. New Delhi, Hamdard National Foundation Monograph, 1985.

52. Deodhar SD, Sethi R, Srimal RC. Preliminary study on anti-rheumatic activity of curcumin (diferuloyl methane). Indian journal of medical research, 1980, 71:632–634.

53. Satoskar RR, Shah Shenoy SG. Evaluation of antiinflammatory property of curcumin (diferuloyl methane) in patient with postoperative inflammation. International journal of clinical pharmacology, therapy and toxicology, 1986, 24:651–654.

54. Rockwell P, Raw I. A mutagenic screening of various herbs, spices and food additives. Nutrition and cancer, 1979, 1:10–15.

55. Yamamoto H, Mizutani T, Nomura H. Studies on the mutagenicity of crude drug extracts. I. Yakugaku zasshi, 1982, 102:596–601.

56. Nagabhushan M, Bhide SV. Nonmutagenicity of curcumin and its antimutagenic action versus chili and capsaicin. Nutrition and cancer, 1986, 8:201–210.

57. Garg SK. Effect of Curcuma longa (rhizomes) on fertility in experimental animals. Planta medica, 1974, 26:225–227.

58. Vijayalaxmi. Genetic effects of tumeric and curcumin in mice and rats. Mutation research, 1980, 79:125–132.

59. Farnsworth NF, Bunyapraphatsara N, eds. Thai medicinal plants, recommended for a primary health care system. Bangkok, Prachachon, 1992.

60. Seetharam KA, Pasricha JS. Condiments and contact dermatitis of the finger-tips. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology, 1987, 53:325–328.

61. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Behradmanesh S, Kheiri S, Nasri H. Association of serum uric acid with level of blood pressure in type 2 diabetic patients. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2014;8(2):152–4.[PubMed]

62. Delfan B, Bahmani M, Hassanzadazar H, Saki K, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Identification of medicinal plants affecting on headaches and migraines in Lorestan Province, West of Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7S1:S376–9. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60261-3. [PubMed] [Cross Ref

63. Amini FG, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Nematbakhsh M, Baradaran A, Nasri H. Ameliorative effects of metformin on renal histologic and biochemical alterations of gentamicin-induced renal toxicity in Wistar rats. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(7):621–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

64. Parsaei P, Karimi M, Asadi SY, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Bioactive components and preventive effect of green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract on post-laparotomy intra-abdominal adhesion in rats. Int J Surg. 2013; 11(9):811–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.08.014. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

65. Hosseini-asl K, Rafieian-kopaei M. Can patients with active duodenal ulcer fast Ramadan? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97(9):2471–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06011.x. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

66. Roohafza H, Sarrafzadegan N, Sadeghi M, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Sajjadi F, Khosravi-Boroujeni H. The association between stress levels and food consumption among Iranian population. Arch Iran Med. 2013; 16(3):145–8. [PubMed]

67. Asadbeigi M, Mohammadi T, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Saki K, Bahmani M, Delfan M. Traditional effects of medicinal plants in the treatment of respiratory diseases and disorders: an ethnobotanical study in the Urmia. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7S1:S364–8. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60259-5. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

68. Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Mohammadifard N, Sarrafzadegan N, Sajjadi F, Maghroun M, Khosravi A, et al. Potato consumption and cardiovascular disease risk factors among Iranian population. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2012; 63(8):913–20. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2012.690024. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

69. Khosravi-Boroujeni H, Sarrafzadegan N, Mohammadifard N, Sajjadi F, Maghroun M, Asgari S, et al. White rice consumption and CVD risk factors among Iranian population. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(2):252–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

70. Behradmanesh S, Horestani MK, Baradaran A, Nasri H. Association of serum uric acid with proteinuria in type 2 diabetic patients. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(1):44–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

71. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Gray AM, Spencer PS, Sewell RD. Contrasting actions of acute or chronic paroxetine and fluvoxamine on morphine withdrawal-induced place conditioning. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275(2):185–9. [PubMed

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT editor-in-chief@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE