ABOUT AUTHORS:

Khandelwal Pankaj, Chirag Sudani*, Parmar Jatin, Prashant Sanghavi, Shifalee Magazine

Mahatma Gandhi College of Pharmaceutical Sciences,

Jaipur.

*patel_chirag75@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This review paper highlights the current advances in knowledge about the safety, efficacy, quality control and regulatory aspects of Phytopharmaceuticals. The growing use of Phytopharmaceuticals (drug and other products derived from plants) by the public is forcing moves to evaluate the health claims of these agents and to develop standards of quality and manufacture. At present there is almost no policy worth its name to regulate the procurement and sale of medicinal plants in developing countries. Finally, the trend in the domestication, production and biotechnological studies and genetic improvement of medicinal plants, instead of the use of plants harvested in the wild, will offer great advantages, since it will be possible to obtain uniform and high quality raw materials which are fundamental to the efficacy and safety of herbal drugs.It is clear that the herbal industry needs to follow strict guidelines and that regulations are needed. This paper presents the element of methods of different aspects on efficacy, safety, quality control and standardization of herbal drugs and formulation. It is followed by international guidelines of WHO for manufacture quality control and evaluation of botanicals. Herbal drugs regulations in India is discussed in detail, followed by an overview of regulatory status of herbal medicine in USA, China, Australia, Brazil, Canada and Germany.

REFERENCE ID: PHARMATUTOR-ART-2005

INTRODUCTION

Herbal drugs are defined as “the art and science of restoring a sufferer to health by the use of plant remedies”. According to European Union definitions, herbal medicinal products (medicines) are “medicinal products containing as active ingredients exclusively plant material and/or vegetable drug preparations.’’ Herbal drug technology includes all the steps that are involved in converting botanical materials into medicines, where standardization and quality control with proper integration of modern scientific techniques and traditional knowledge will remain important.

According to WHO global survey on the national policy and regulation of traditional medicine, there are three common difficulties and challenges: lack of information sharing; lack of safety monitoring of herbal medicines; and lack of methods to evaluate the safety and efficacy. Correct identification and quality assurance of the starting material is, therefore, an essential prerequisite to ensure reproducible quality of herbal medicine, which contributes to its safety and efficacy. Therefore a phytopharmaceutical want to be regarded as rational drugs, they need to be standardized and pharmaceutical quality must be approved. Also, in pharmacological, toxicological and clinical studies with herbal drugs, their composition needs to be well documented in order to obtain reproducible results. The WHO has recognized this problem and published guidelines to ensure the reliability and repeatability of research on herbal medicines.

Currently, the major pharmaceutical companies have demonstrated renewed interest in investigating higher plants as sources for new lead structures and also for the development of standardized phototherapeutics agents with proven efficacy, safety and quality. Phototherapeutics are normally marketed as standardized preparations in the form of liquid, solid (powdered extract) or viscous preparations. They are prepared by maceration, percolation or distillation (volatile oils).

Inspite of the widespread usage of herbal pharmaceuticals there is a lack of proper standardization and quality control of the drugs. The problem is often due to the special characters associated with plant origin medicines when compared with well-defined synthetic drugs. These are:

- The active constituents of herbal drugs are not well established.

- Standardization, stability and quality control testing are relatively time consuming, tedious and highly priced.

- Genuine raw materials are not easily found.

- Herbal drugs are mixtures of many constituents

- The active principle(s) is (are) hardly known

- Selective analytical methods may not yet exist

- Reference compounds may not be available commercially

- Chemical variability of plant material

- Natural variation/biodiversity

- Influence of harvest, drying, and storage conditions

- They have a wide range of therapeutic use and are suitable for chronic treatments.

- The occurrence of undesirable side effects seems to be less frequent with herbal medicines, but well-controlled randomized clinical trials have revealed that they also exist.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

THE NEED FOR SAFETY, EFFICACY AND QUALITY CONTROL:

Pharmaceutical products used as medicines are usually single chemical entities with specific actions at receptors, enzymes and other cellular sites. These drugs or preparations are marketed after vigorous clinical trials to support rational pharmacotherapy. The most important question regarding any drug to be used is how safe it is for clinical use. Unfortunately this aspect is not addressed or transparent to the consumers who want to use the herbal formulation. The herbal formulations which are sold as over the counter (OTC) have a different protocol regarding preparation, acquiring license and marketing. The active principles of herbal preparations are not often well defined. Regulations regarding safety and efficacy are not known to scientists or consumers.

Moreover as these are thought to be "natural", many people believe that they are safe. In addition to this, society's growing interest in herbal products and other dietary supplements stems from a disappointment in allopathic medicine which often results in blind acceptance. However, herbal products can be as toxic as or even more toxic than prescription medicine. They can also have unwanted side effects, cause drug interactions and possibly create surgical problems. Another problem is that people tend to rely more on testimonials on the benefits of herbal products than solid, scientific evidence all precautions that are taken with conventional medications should apply to herbal medications. Children, pregnant, and breast-feeding women should not use herbal therapies as the OTC product. Another issue that applies to both conventional and herbal medications is the potential for drug interactions. Most herb-drug interaction concerns include high-dose antioxidants and vitamins usage during chemotherapy, estrogenic properties of supplements, and blood thinning properties of supplements. According to a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), roughly 15 million adults are at risk of possible adverse interactions between prescription medicines and herbs.[7, 8, 9, 10]

Table 1: Common herbal-drug interactions [11-19]

|

Herbal drugs |

Interaction |

Patients that should avoid use |

|

Antioxidant drugs: |

May interfere with cancer cell killing effects of certain chemotherapy and radiation therapy |

Patients undergoing radiation therapy and |

|

Estrogenic activity : |

|

|

|

Blood thinning properties: |

|

|

|

Photosensivity properties |

Increase skin sensitivity or responsiveness to sunlight |

Patients undergoing radiation therapy |

Parameters for Quality Control of Herbal Drugs:

A. Microscopic Evaluation:

Quality control of herbal drugs has traditionally been based on appearance and today microscopic evaluation is indispensable in the initial identification of herbs, as well as in identifying small fragments of crude or powdered herbs, and detection of foreign matter and adulterants. A primary visual evaluation, which seldom needs more than a simple magnifying lens, can be used to ensure that the plant is of the required species, and that the right part of the plant is being used. At other times, microscopic analysis is needed to determine the correct species and/or that the correct part of the species is present.

For instance, pollen morphology may be used in the case of flowers to identify the species, and the presence of certain microscopic structures such as leaf stomata can be used to identify the plant part used. Although this may seem obvious, it is of prime importance, especially when different parts of the same plant are to be used for different treatments. Stinging nettle is a classic example where the aerial parts are used to treat rheumatism, while the roots are applied for benign prostate hyperplasia.

B. Determination of Foreign Matter:

Herbal drugs should be made from the stated part of the plant and be devoid of other parts of the same plant or other plants. They should be entirely free from moulds or insects, including excreta and visible contaminant such as sand and stones, poisonous and harmful foreign matter and chemical residues. Macroscopic examination can easily be employed to determine the presence of foreign matter, although microscopy is indispensable in certain special cases. Furthermore, when foreign matter consists, for example, of a chemical residue, TLC is often needed to detect the contaminants.

C. Determination of Ash:

To determine ash content the plant material is burnt and the residual ash is measured as total and acid-insoluble ash. Total ash is the measure of the total amount of material left after burning and includes ash derived from the part of the plant itselfand acid-insoluble ash.

The latter is the residue obtained after boiling the total ashwith dilute hydrochloric acid, and burning the remaining insoluble matter.

The second procedure measures the amount of silica present, especially in the form ofsand and siliceous earth.

D. Determination of Heavy Metals:

Contamination by toxic metals can either be accidental or intentional. Contamination by heavy metals such as mercury, lead, copper, cadmium, and arsenic in herbal remedies can be attributed to many causes, including environmental pollution, and can pose clinically relevant dangers for the health of the user and should therefore be limited. The potential intake of the toxic metal can be estimated on the basis of the level of its presence in the product and the recommended or estimated dosage of the product.

A simple, straightforward determination of heavy metals can be found in many pharmacopeias and is based on color reactions with special reagents such as thioacetamide or diethyldithiocarbamate, and the amount present is estimated by comparison with a standard. Instrumental analyses have to be employed when the metals are present in trace quantities, in admixture, or when the analyses have to be quantitative. The main methods commonly used are atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS), inductively coupled plasma (ICP) and neutron activation analysis (NAA).

E. Determination of Microbial Contaminants and Aflatoxins:

Medicinal plants may be associated with a broad variety of microbial contaminants, represented by bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Inevitably, this microbiological background depends on several environmental factors and exerts an important impact on the overall quality of herbal products and preparations. Herbal drugs normally carry a number of bacteria and molds, often originating in the soil. Poor methods of harvesting, cleaning, drying, handling, and storage may also cause additional contamination, as may be the case with Escherichia coli or Salmonella spp.

Laboratory procedures investigating microbial contaminations are laid down in the well-known Pharmacopeias, as well as in the WHO guidelines. In general, a complete procedure consists of determining the total aerobic microbial count, the total fungal count, and the total Enterobacteriaceae count, together with tests for the presence of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella spp. The presence of fungi should be carefully investigated and/or monitored, since some common species produce toxins, especially aflotoxins. Aflatoxins in herbal drugs can be dangerous to health even if they are absorbed in minute amounts.

Aflatoxin-producing fungi sometimes build up during storage. Procedures for the determination of aflatoxin contamination in herbal drugs are published by the WHO. After a thorough clean-up procedure, TLC is used for confirmation. In addition to the risk of bacterial and viral contamination, herbal remedies may also be contaminated with microbial toxins, and as such, bacterial endotoxins and mycotoxins, at times may also be an issue. There is evidence that medicinal plants from some countries may be contaminated with toxigenic fungi (Aspergillus, Fusarium).

F. Determination of Pesticide Residues:

Even though there are no serious reports of toxicity due to the presence of pesticides and fumigants, it is important that herbs and herbal products are free of these chemicals or at least are controlled for the absence of unsafe levels.

Herbal drugs are liable to contain pesticide residues, which accumulate from agricultural practices, such as spraying, treatment of soils during cultivation, and administering of fumigants during storage. However, it may be desirable to test herbal drugs for broad groups in general, rather than for individual pesticides. Many pesticides contain chlorine in the molecule, which, for example, can be measured by analysis of total organic chlorine. In an analogous way, insecticides containing phosphate can be detected by measuring total organic phosphorus. Samples of herbal material are extracted by a standard procedure, impurities are removed by partition and/or adsorption, and individual pesticides are measured by GC, MS, or GC/MS. Some simple procedures have been published by the WHO and the European Pharamacopoeia has laid down general limits for pesticide residues in medicine.

G. Determination of Radioactive Contamination:

There are many sources of ionization radiation, including radionuclides, occurring in the environment. Hence a certain degree of exposure is inevitable. Dangerous contamination, however, may be the consequence of a nuclear accident. The WHO, in close cooperation with several other international organizations, has developed guidelines in the event of a widespread contamination by radionuclides resulting from major nuclear accidents. These publications emphasize that the health risk, in general, due to radioactive contamination from naturally Occurring radio nuclides is not a real concern, but those arising from major nuclear accidents

such as the nuclear accident in Chernobyl, may be serious and depend on the specific radionuclide, the level of contamination, and the quantity of the contaminant consumed. Taking into account the quantity of herbal medicine normally consumed by an individual, they are unlikely to be a health risk. Therefore, at present, no limits are proposed for radioactive contamination.

H. Analytical Methods

When pharmacopeial monographs are unavailable, development and validation of analytical procedures have to be carried out by the manufacturer. The best strategy is to follow closely the pharmacopeial definitions of identity, purity, and content or assay. The plant or plant extract can be evaluated by various biological methods to determine pharmacological activity, potency, and toxicity. A simple chromatographic technique such as TLC may provide valuable additional information to establish the identity of the plant material. This is especially important for those species that contain different active constituents. Qualitative and quantitative information can be gathered concerning the presence or absence of metabolites or breakdown products. The instruments for UV-VIS determinations are easy to operate, and validation procedures are straightforward but at the same time precise. Although measurements are made rapidly, sample preparation can be time consuming and works well only for less complex samples, and those compounds with absorbance in the UV-VIS region. HPLC is the preferred method for quantitative analysis of more complex mixtures. Though the separation of volatile components such as essential and fatty oils can be achieved with HPLC, it is best performed by GC or GC/MS.

The quantitative determination of constituents has been made easy by recent developments in analytical instrumentation. Recent advances in the isolation, purification, and structure elucidation of naturally occurring metabolites have made it possible to establish appropriate strategies for the determination and analysis of quality and the process of standardization of herbal preparations. Classification of plants and organisms by their chemical constituents is referred to as chemotaxonomy. TLC, HPLC, GC, quantitative TLC (QTLC), and high-performance TLC (HPTLC) can determine the homogeneity of a plant extract.

Over-pressured layer chromatography (OPLC), infrared and UV-VIS spectrometry, MS, GC, liquid chromatography (LC) used alone, or in combinations such as GC/MS, LC/MS, and

MS/MS, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), electrophoretic techniques, especially by hyphenated chromatographies, are powerful tools, often used for standardization and to control the quality of both the raw material and the finished product.[20-32]

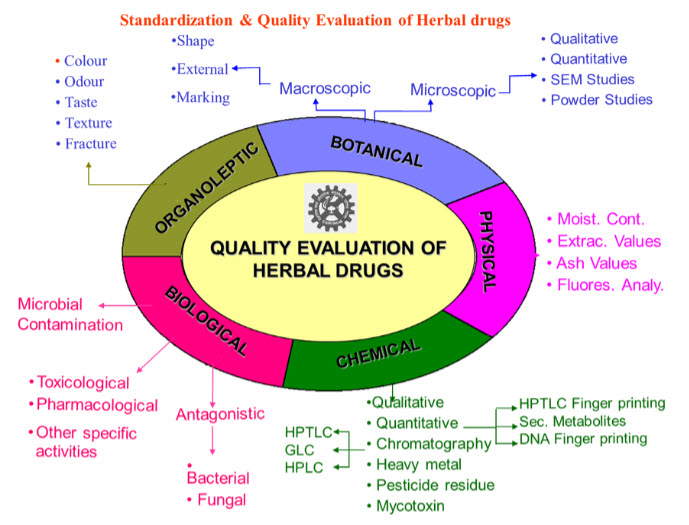

Fig: 1. Schematic Diagram of for Quality Control of Herbal Drugs:

REGULATORY GUIDELINES:

The legal process of regulation and legislation of herbal medicines changes from country to country. The reason for this involves mainly cultural aspects and also the fact that herbal medicines are rarely studied scientifically. Thus, few herbal preparations have been tested for safety and efficacy. Several regulatory models for herbal medicines currently exist, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, traditional medicines and dietary supplements. Thus, the need to establish global and/or regional regulatory mechanisms for regulating herbal drugs seems obvious. A summary of the regulatory processes related to herbal drugs in some selected countries is presented below:

1. WHO GUIDELINES:

The WHO has published guidelines in order to define basic criteria for evaluating the quality, safety, and efficacy of herbal medicines aimed at assisting national regulatory authorities, scientific organizations and manufacturers in this particular area. Furthermore, the WHO has prepared pharmacopoeic monographs on herbal medicines and the basis of guidelines for the assessment of herbal drugs. WHO has clearly delineated the various steps required for authenticating, standardizing and validating the various phytopharmaceuticals.

2. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In the USA, herbal remedies are referred to as homeopathic remedies. All such remedie, because these are offered for treatment of disease, are regarded as drugs. This means that if a herbal remedy is included in United States Pharmacopoeia, the official Homeopathic Pharmacopoeia or the National formulary, it will be recognized officially as a drug. The only way that a drug application for its intended use in USA is by approval of new drug application by the Food and Drug Administration. Up till now, no homeopathic drug has been approved for administration under a New Drug Application. This however does not necessarily mean that it is illegal to market these herbal preparations. These could be marketed without the approval of the Food and Drug Administration in certain circumstances. All marketed drugs have to be listed with the Food and Drug Administration.

3. US FDA GUIDELINE:

The US FDA has issued draft guidance for botanical products. The regulatory approach is based on:

1. Intended use of botanical – as dietary supplement, cosmetic or drug and

2. Status of botanical – marketed in US, marketed outside US or not marketed at all. The guideline is fairly exhaustive and pragmatic.

Some of the general guidelines are:

* Traditional herbal medicines or currently marketed botanical products, because of their extensive though uncontrolled use in humans, may require less preclinical information to support initial clinical trials than would be expected for synthetic or highly purified drugs.

* Requirements for Investigational New Drug (IND) applications of botanicals legally marketed in the United States as dietary supplements or cosmetics.

- Very little new chemistry manufacturing and controls (CMC) or toxicologic data are needed to initiate early clinical, if there are no known safety issues associated with the product and it is used at approximately the same doses as those currently or traditionally used or recommended.

- As the product is marketed and the dose thought to be appropriate and well tolerated is known, there should be little need for pilot or typical Phase 1 studies. Sponsors are allowed to initiate more definitive efficacy trials early in the development program. If there is doubt about the best dose of the product tested, a randomized, parallel, dose-response study may be particularly useful as an initial trial.

* Requirements for botanical product that has not been previously marketed in the United States or anywhere in the world

- Certain additional information (CMC, toxicology, human use) is required to assist FDA in determining the safety of the product for use in initial clinical studies.

- If the product is prepared, processed, and used according to methodologies for which there is prior human experience, sufficient information may be available to support such studies without standard preclinical testing.

* Clinical trials of herbal products

- There may be special problems associated with the incorporation of traditional methodologies, such as selection of doses and addition of new botanical ingredients based on response, which will need to be resolved.

- The credible design for clinical trials studies will be randomized, double blind, and placebo-controlled (or dose-response). For most conditions potentially treated by botanical drugs (generally mildly symptomatic), active control equivalence designs would not be credible.

4. EUROPEAN UNION (EU)

In EU, herbs are more strictly regulated. The European agency of evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMFA) provides general guidelines for setting uniform set of specifications for botanical preparations manufactured and sold in Europe. These guidelines for assessing quality of herbal preparations for tests, procedures, and acceptance criteria used to assure the quality of botanical preparations at release and during its shelf life. The norms consider the marketing approval of herbal products (including fixed combinations). Specific guideline also addresses the assessment of safety and efficacy. The strategy is to follow the concept of evidence based on medicine.

5. ARGENTINA

The Herboristerias are authorized for sale as plant drugs but not as mixtures. Mixtures of plant drugs are controlled. In 1993, a Ministry of Health regulation determined the obligatory registration of medicinal herbs. The Argentinian National Pharmacopea established control over the existence of crude extracts, extracts or fractions of complex chemical composition, and pure active principles. About 889 monographs exist in Argentina. About 56 describe crude drugs alone and 33 describe extracts or fractions. However, there is lack of control of raw materials, lack of control over the wild plant, lack of scientific criteria for the collection of plants, and lack of control over methods of drying, conservation or grinding.

6. CHINA

In China, it is quite legal to sell medicinal plants and herbal in the free market, both in rural and urban areas .This would account for a large volume of the use of herbal remedies in the country. However, if a new medicinal plant product or a crude drug is to be imported from abroad to be sold in the Chinese market, then the approval of the provincial department of public health is required. The Pharmacopoeia People’s Republic of China has got a section on “Standard for Processing of Chinese Materia Medica”. This new plant material or crude material being imported will have to be assessed according to the standards in the Pharmacopoeia and approval either given or not given. The origin of crude drug or the of herbal product must always be clearly marked.

If Chinese herbal medicines are produced in factories either for export or for local use in other parts of the country, these have to be undergo quality control tests before being released. Each factory has its own quality control unit which checks on the quality of different samples of product.

Another set of rigid criteria has been laid down for assessing patented traditional Chinese medicines. While applying for permission to market these medicines, the manufacturer will need to list the main ingredient and the other ingredients. The reviewing authorities will review this compound according to the concepts and practice of Chinese traditional medicine and will also observe closely whether there are may be incompatibility between the different ingredients. Only after assuring themselves that the product conforms to the Chinese traditional system of medicines, that it is safe and that the ingredients are not incompatible with each other will the patent medicine be allowed to be released to the market.

7. AUSTRALIA

The Australian Parliament established the Working Party on Natural and Nutritional Supplements to review the quality, safety, efficacy and labelling of herbal and related products (Therapeutic Good Act, 1990). The act provides: that traditional claims for herbal remedies be allowed, providing general advertising requirements are complied with and providing such claims are justified by literature references.

8. BRAZIL

Despite its immense flora, cultural aspect and the widespread use of herbal medicine, so far few efforts have been made in Brazil to establish the quality, safety and efficacy of these products. In 1994, the Ministry of Health created a commission to evaluate the situation of phytotherapeutic agents in Brazil. The commission proposed a directive based mainly on German and French regulations and on WHO guidelines for herbal drugs. In 1995, Directive Number 6 established the legal requirement for the registration of herbal drugs and defined the phytopharmaceutical product as .a processed drug containing as active ingredients exclusively plant material and/or plant drug preparations. They are intended to treat, cure, alleviate, prevent and diagnose diseases. The legal requirements for registration of herbal medicines in Brazil demand complete documentation of efficacy, safety and welldefined quality control. For old medicinal herbs already registered, the law established 5 and 10 years for the assessment of their safety and efficacy, respectively. Due to the resistance of some companies, this law has not yet been enforced.

9. CANADA

In 1986, the Canadian Health Protection Branch (HPB) constituted a special committee and classified herbal drugs as. Folk Medicine. The regulation is based on traditional uses, as long as the claim is validated by scientific studies. In 1990, the HPB listed 64 herbs that were considered to be unsafe. In 1992, the HPB submitted a regulatory proposal to the Canadian Parliament and listed another 64 herbs that were considered to be adulterants. The Canadian regulatory system is consistent with WHO guidelines for the assessment of herbal medicines.

10. GERMANY

Germany’s Commission E (phytotherapy and herbal substances) was established in 1978. It is an independent division of the German Federal Health Agency that collects information on herbal medicines and evaluates them for safety and efficacy. The following methods and criteria are followed by Commission E: 1) traditional use; 2) chemical data; 3) experimental, pharmacological and toxicological studies; 4) clinical studies; 5) field and epidemiological studies; 6) patient case records submitted from physician’s files, and 7) additional studies, including unpublished proprietary data submitted by manufacturers. Two kinds of monographs are prepared: monopreparations and fixed combinations. The composition of Commission E is as follows: physicians, pharmacists, pharmacologists, toxicologists, industry representatives and laypersons, for a total of 24 members. Three possibilities for marketing herbal drugs exist: 1) temporary marking authorization for old herbal drugs until they are evaluated for safety and efficacy; 2) monographs of standardized marketing authorization, and 3) individual marketing authorization. Evaluations are published in the form of monographs that approve or disapprove the herbal drugs for over-the-counter use. Herbal medicines are sold in pharmacies, drugstores and health food stores. Some herbal medicines are controlled by a physician’s prescription. Commission E has published about 300 monographs: 200 positives and 100 negatives. About 600-700 plants are sold in Germany. Approximately 70% of physicians prescribe registered herbal drugs. Part of annual sales is paid for by government health insurance. [34-41]

CONCLUSION

Phytopharmaceuticals/Herbal medicine has become a topic of increasing global importance, with both medicinal and economic implications. Widespread and growing use of herbs has created public health challenges globally in terms of quality, safety and efficacy. Standardization of methods and quality control data on safety and efficacy are required for proper understanding of the use of herbal medicines. The efficacy and safety of any pharmaceutical product is determined by the compounds (desired and undesired) which it contains. The purpose of quality control is to ensure that each dosage unit of the drug product delivers the same amount of active ingredients and is, as far as possible, free of impurities. As herbal medicinal products are complex mixtures which originate from biological sources, great efforts are necessary to guarantee a constant and adequate quality.

Finally, the trend in the domestication, production and biotechnological studies and genetic improvement of medicinal plants, instead of the use of plants harvested in the wild, will offer great advantages, since it will be possible to obtain uniform and high quality raw materials which are fundamental to the efficacy and safety of herbal drugs.

REFERENCES:

1.Sharma R.K. and Arora R., Herbal drugs: Regulation across the globe. Herbal Drugs – A Twenty First Century Perspective (1st ed.). JAYPEE Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., New Delhi; 625-627 (2006).

2.Verpoorte R. and Mukherjee P.K., Overview of global regulatory status. GMP For Botanicals – Regulatory and Quality Issues on Phytomedicines (1st ed.). Business Horizons Pharmaceutical Publishers, New Delhi; 22-27, 41. (2003).

3.Blumenthal M., Herbal Gram, 45: 68. (1999).

4.Brevoort P., Herbal Gram, 36:49-59. (1995).

5.De Smet, PAGM. Drugs, 54: 801-840. (1997).

6.Editorial, Lancet, 343: 1513-1515.(1994).

7.Warude D. and Patwardhan B., Botanicals: Quality and regulatory issues. Journal of scientific and industrial research. 64: 83-92 (2005).

8.Gaedcke F., Dtsch Apoth Ztg. 131:2551–2555(1991).

9.Chalmer C. T., Centre for Systemic Review, Children Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Canada. (2000).

10.Anglee M. K, Moss J, & Yuan C. S., JAMA (286) pp 208-216. (2001).

11.Herr S.M., Herb-Drug Interaction Handbook, 3rd Edn. ISBN 0967877326, (2005).

12.Barnes J, Anderson L. A, & Phillipson J.D., J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 53, 583. (2001)

13.Smolinske S.C., J. Am. Med. Women’s Assoc. 1999, 54, 191.

14.Fugh-Berman, A. Lancet 2000, 355, 144.

15.Meneilly G., Top ten tips for avoiding drug-herb interactions. Living + 2000, bcpwa.org/issue6/tentips.htm. Accessed January 2013.

16.Ernst E., Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003, 162, 72.

17.Janetzky K, Morreale A.P., Am. J.Health Syst. Pharm. 1997, 54, 692.

18.Jowell T., Herbal Medicines. House of Commons official report (Hansard).1999, 26, 426.

19. Mathews J., Holisticonline.com 1998–2005. holisticonline.com/alt_medicine/altmed_definitions.htm. Accessed March 2013.

20.AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18th edn. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD, 2005.

21.WHO. Quality Control Methods for Medicinal Plant Materials, World Health Organization, Geneva, 1998.

22.WHO. Quality Control Methods for Medicinal Plant Materials. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1999.

23.WHO. The International Pharmacopeia, Vol. 1: General Methods of Analysis, 3rd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1979.

24.WHO. The International Pharmacopeia, Vol. 2: Quality Specifications, 3rd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1981.

25.De Smet, Keller K, Hansel R, & Chandler R.F., Adverse Effects of Herbal Drugs, Vol. 1. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, 1992.

26.Lazarowych N. & Pekos P., Drug Inf. J. 1998, 32, 497.

27.WHO. The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2000–2202 (WHO/PCS/01.5). International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000.

28.Anonymous. European Pharmacopoeia, 3rd edn. Strasbourg Council of Europe, 1996.

29.Farber J.M, Carter A.O, Varughese P.V, Ashton F.E, & Ewan E.P., New Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 338.

30.Kneifel W. & Czech E., B Planta Med. 2002.

31.Sinha K.K., Mycotoxins in Agriculture and Food Safety. Marcel Dekker, New York, 1998.

32.Rozylo J.K, Zabinska A, Matysiak J, & Niewiadomy A. J., Chromatogr. Sci. 2002, 40, 581.

33.Bilia A.R, Bergonzi M.C, Lazari D, & Vincieri F.F., J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5016.

34.Ebel S, Gigalke H.J, & Voelkl S., AMDHPTLC Analysis of Medicinal Plants. Proceedings of 4th International Symposium of Instrumental HPTLC, Selvino/Bargamo at Italy, 1987, p. 113.

35.Farnsworth N.R, Henry L.K, Svoboda G.H, Blomster R.N., & Fong H.S., J. Lloydia 1968, 35, 35.

36.WHO. The International Pharmacopeia, Vol. 4: Test Methods and General Requirements. Quality Specifications for Pharmaceutical Substances, Excipients, and Dosage Forms, 3rd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1994.

37.WHO. The International Pharmacopeia, Vol. 2: Quality Specifications, 3rd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva,

38.Calixto J.B., Efficacy, safety, quality control, marketing and regulatory guidelines for herbal medicines (phytotherapeutic agents). Brazilian journal of Medical and Biological Research. 33: 179-189 (2000).

39.Regulatory Issues for Traditional Medicine – Herbal Research. Accessed at Feb. 2013.

40.Warude D. and Patwardhan B., Botanicals: Quality and regulatory issues. Journal of scientific and industrial research. 64: 83-92 (2005).

41.Chaudhry R.D., Regulatory Requirements. Herbal Dug Industry – A Practical Approach to Industrial Pharmacognosy (1st ed.). Eastern Publishers, New Delhi; 537-546 (1996).

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE