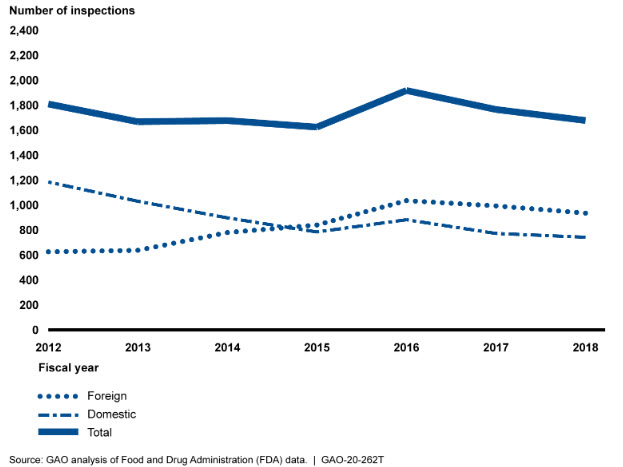

As per analysis of United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), preliminary analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data shows that from fiscal year 2012 through 2016, the number of foreign drug manufacturing establishment inspections increased. From fiscal year 2016 through 2018, both foreign and domestic inspections decreased by about 10 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

Howevever, the total number of foreign inspections surpassed the number of domestic inspections in 2015, and a growing percentage of FDA’s foreign inspections (43 percent in 2018) were conducted in China and India, where most establishments that ship drugs to the United States were located. FDA officials attributed the decline, in part, to vacancies among investigators available to conduct inspections. GAO previously noted the vital role that inspections play in FDA’s oversight of foreign establishments.

Drugs sold in the United States, including active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished dosage forms—are manufactured throughout the world. According to a May 2019 FDA report, in fiscal year 2018 about 40 percent of establishments manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market were located domestically and more than 60 percent of establishments manufacturing for the U.S. market were located overseas.As of March 2019, FDA data show that India and China had the most manufacturing establishments shipping drugs to the United States, with about 40 percent of all foreign establishments in these two countries.

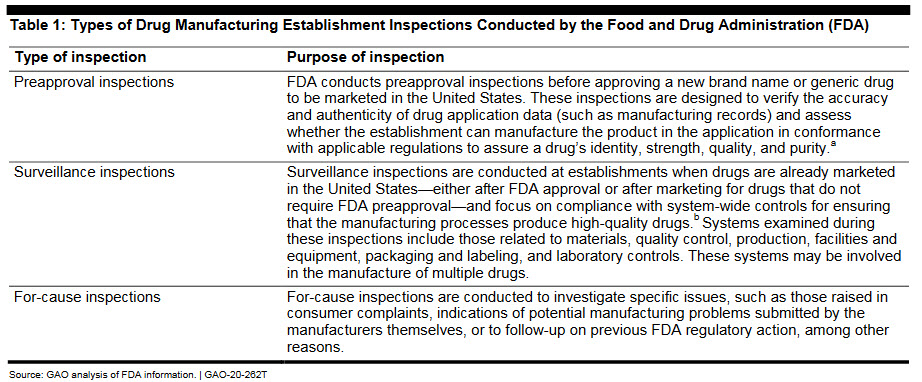

Types of Inspection

Drugs manufactured overseas must meet the same statutory and regulatory requirements as those manufactured in the United States. FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) establishes standards for the safety, quality, and effectiveness of, and manufacturing processes for, over-the-counter and prescription drugs. CDER requests that FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) inspect both domestic and foreign establishments to ensure that drugs are produced in conformance with applicable laws of the United States, including current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) regulations.FDA investigators generally conduct three main types of drug manufacturing establishment inspections: preapproval inspections, surveillance inspections, and for-cause inspections, as described in below table. At times, FDA may conduct an inspection that combines both preapproval and surveillance inspection components in a single visit to an establishment.

FDA uses multiple databases to select foreign and domestic establishments for surveillance inspections, including its registration database and inspection database. Because the establishments are continuously changing as they begin, stop, or resume marketing products in the United States, CDER creates an establishment catalog monthly. The catalog is prioritized for inspection twice each year.

FDA Inspection Workforce

Investigators from ORA and, as needed, ORA laboratory analysts with certain expertise are responsible for inspecting drug manufacturing establishments.16 FDA primarily relies on three groups of investigators to conduct foreign inspections:

• ORA investigators based in the United States, who primarily conduct domestic drug establishment inspections but may sometimes conduct foreign inspections.

• Members of ORA’s dedicated foreign drug cadre, a group of domestically based investigators, who exclusively conduct foreign inspections.

• Investigators assigned to and living in the countries where FDA has foreign offices, including staff based in the foreign offices full time and those on temporary duty assignment to the foreign offices. FDA began opening offices around the world in 2008 to obtain better information on the increasing number of products coming into the United States from overseas, to build relationships with foreign stakeholders, and to perform inspections.17 FDA full-time foreign office staff are posted overseas for 2-year assignments. FDA staff can also be assigned to the foreign offices on temporary duty assignments for up to 120 days. In fiscal year 2019, there were full-time and temporary duty drug investigators assigned to FDA foreign offices in China and India.

Post-Inspection Activities

FDA’s process for determining whether a foreign establishment complies with CGMPs involves both CDER and ORA. During an inspection, ORA investigators are responsible for identifying any significant objectionable conditions and practices and reporting these to the establishment’s management. Investigators suggest that the establishment respond to FDA in writing concerning all actions taken to address the issues identified during the inspection.

Once ORA investigators complete an inspection, they are responsible for preparing an establishment inspection report to document their inspection findings. Inspection reports describe the manufacturing operations observed during the inspection and any conditions that may violate U.S. statutes and regulations. Based on their inspection findings, ORA investigators make an initial recommendation regarding whether regulatory actions are needed to address identified deficiencies using one of three classifications: no action indicated (NAI); voluntary action indicated (VAI); or official action indicated (OAI). Inspection reports and initial classification recommendations for regulatory action are to be reviewed within ORA. For inspections classified as OAI—where ORA identified serious deficiencies—such inspection reports and classification recommendations are to be reviewed within CDER. CDER is to review the ORA recommendations and determine whether regulatory action is necessary. CDER also is to review inspection reports and initial classification recommendations for all for-cause inspections, regardless of whether regulatory action is recommended by ORA.

According to FDA policy, inspections classified as OAI may result in regulatory action, such as the issuance of a warning letter. FDA issues warning letters to those establishments manufacturing drugs for the U.S. market that are in violation of applicable U.S. laws and regulations and may be subject to enforcement action if the violations are not promptly and adequately corrected. In addition, warning letters may notify foreign establishments that FDA may refuse entry of their drugs at the border or recommend disapproval of any new drug applications listing the establishment until sufficient corrections are made. FDA may take other regulatory actions if it identifies serious deficiencies during the inspection of a foreign establishment. For example, FDA may issue an import alert, which instructs FDA staff that they may detain drugs manufactured by the violative establishment that have been offered for entry into the United States. In addition, FDA may conduct regulatory meetings with the violative establishment. Regulatory meetings may be held in a variety of situations, such as a follow-up to the issuance of a warning letter to emphasize the significance of the deficiencies or to communicate documented deficiencies that do not warrant the issuance of a warning letter.

Total Number of FDA Foreign Drug Inspections Has Decreased Since Fiscal Year 2016 after Several Years of Increases

Preliminary analysis of FDA data shows that from fiscal year 2012 through fiscal year 2016, the number of FDA foreign drug manufacturing establishment inspections increased but then began to decline after fiscal year 2016 (see fig. 2). In fiscal year 2015, the total number of foreign inspections surpassed the number of domestic inspections. From fiscal year 2016 to 2018, both foreign and domestic inspections decreased—by about 10 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

FDA continues to conduct the largest number of foreign inspections in India and China, with inspections in these two countries representing about 40 percent of all foreign drug inspections from fiscal year 2016 (when we last reported on this issue) through 2018.

Total number of FDA inspections other than USA

FDA Identified Deficiencies during the Majority of Foreign Inspections

FDA identified deficiencies in approximately 64 percent of foreign drug manufacturing establishment inspections (3,742 of 5,844 inspections). This includes deficiencies necessitating a classification of VAI or the more serious OAI

Inspection ClassificationsBased on their inspection findings, FDA investigators make an initial recommendation regarding the classification of each inspection:

•No action indicated (NAI) means that insignificant or no deficiencies were identified during the inspection.

•Voluntary action indicated (VAI) means that deficiencies were identified during the inspection, but the agency is not prepared to take regulatory action, so any corrective actions are left to the establishment to take voluntarily.

•Official action indicated (OAI) means that serious deficiencies were found that warrant regulatory action.

About 59 percent of domestic inspections (3,702 out of 6,291) identified deficiencies during this time period. This proportion is similar to 2008, when FDA identified deficiencies in about 62 percent of foreign inspections and 51 percent of domestic inspections from fiscal years 2002 through 2006.

serious deficiencies identified during foreign drug inspections classified as OAI—which represented 8 percent of inspections from fiscal year 2012 through 2018—include CGMP violations such as those related to production and process controls, equipment, records and reports, and buildings and facilities. For example:

• Failure to maintain the sanitation of the buildings used in the manufacturing processing, packing, or holding of a drug product (21 C.F.R. § 211.56(a) (2019)). At an establishment in India producing finished drug products, the investigator reported observing a live moth floating in raw material used in the drug production, and that the facility staff continued to manufacture the drug products using the raw material contaminated by the moth, despite the investigator pointing out its presence

• Failure to perform operations relating to the manufacture, processing, and packing of penicillin in facilities separate from those used for other drug products (21 C.F.R. § 211.42 (d) (2019)). At an establishment in Turkey that manufactured penicillin and other drugs, the investigator reported that the manufacturer had detected penicillin outside the penicillin manufacturing area of the establishment multiple times. According to FDA, penicillin contamination of other drugs presents great risk to patient safety, including potential anaphylaxis (even at extremely low levels of exposure) and death.

The identification of serious deficiencies is not unique to foreign inspections. For example, at a domestic establishment producing finished drug products, the investigator observed brown stains, white residues, and brown stagnant water in manufacturing equipment.Some investigators who conduct foreign inspections expressed concern with instances in which ORA or CDER reviewers reclassify the investigator’s initial inspection classification recommendations of OAI to the less serious classification of VAI.

MAIN CHALLENGES TO FDA

FDA continues to face unique challenges when inspecting foreign drug establishments—as compared to domestic establishments—that raise questions about the equivalence of these inspections.

Preannouncing Inspections: The amount of notice FDA generally gives to foreign drug establishments in advance of an inspection is different than for domestic industries. Domestic drug establishment inspections are almost always unannounced, whereas foreign establishments generally receive advance notice of an FDA inspection. Actually, FDA is not required to preannounce foreign inspections. However, FDA does so to avoid wasting agency resources, obtain the establishment’s assistance to make travel arrangements, and ensure the safety of investigators when traveling in country.

The officials estimated that FDA generally gives 12 weeks of notice to establishments that investigators are coming when investigators are traveling from the United States. While local investigators in FDA’s China and India offices do conduct unannounced or short-notice inspections.

Language Barriers: FDA generally does not send translators on inspections in foreign countries. Rather, investigators rely on the pharma industries to provide translation services, which can be an English-speaking employee of the industry being inspected, an external translator hired by the industry, or an English-speaking consultant hired by the industry. This may not be big problem in India but it may be challenging in parts of Asia, including China and Japan.

Lack of Flexibility: There is little flexibility to extend foreign inspections conducted by domestically based investigators because the inspections they conduct on an overseas trip are scheduled back-to-back in 3-week trips that may involve three different countries.

Post-Inspection Classification Process: FDA implemented a new post-inspection classification process: when an ORA investigator recommends an OAI classification following an inspection, ORA compliance is required to send that inspection report to CDER for review within 45 calendar days from the inspection closeout. Among other things, the process was intended to help ensure FDA can communicate inspection results to domestic and foreign establishments within 90 days of the inspection closeout, as committed to under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments of 2017

Post-inspection reporting time frames can create challenges for domestic investigators that conduct foreign inspections and raise questions about the equivalence to domestic inspections.